War on Want and London Mining Network, supported by the Yes to Life, No to Mining network, have launched a new report: Post-Extractivist_Transition

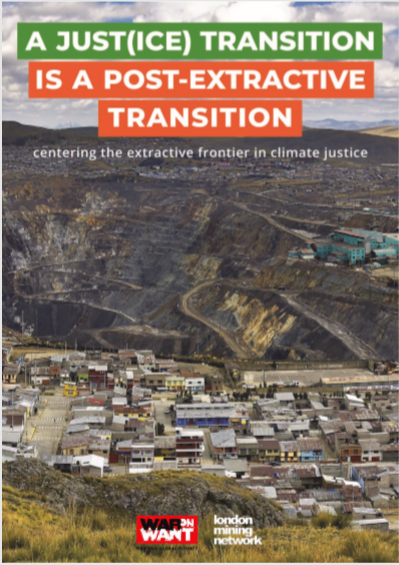

A just(ice) transition is a post-extractive transition

Centering the extractive frontier in climate justice

While the global majority disproportionately suffer the impacts of the climate crisis and the extractivist model, the Global North’s legacy of colonialism, the excess of the world’s wealthiest, and the power of large corporations are responsible for these interrelated crises.

The climate change mitigation commitments thus far made by countries in the Global North are wholly insufficient; not only in terms of emissions reductions, but in their failure to address the root causes of the crisis – systemic and intersecting inequalities and injustices. This failure to take inequality and injustice seriously can be seen in even the most ambitious models of climate mitigation.

This report sets out to explore the social and ecological implications of those models with a focus on metal mining, in six sections:

- Climate justice, just(ice) transition locates the report’s contributions within the broader struggle for climate and environmental justice, explains the reasoning for the report’s focus on mining and emphasizes the social dimension of energy transitions.

- Extractivism in the decades to come discusses projections for total resource extraction over the next four decades and raises concerns about the interconnected ecological impacts of increased resource extraction.

- The transition-mining nexus section places in perspective the significance of renewable energy technologies in driving demand, by examining the share of critical metal end-uses that renewable energy technologies account for relative to other end-uses.

- Greenwashing, political will and investment trends expose how the mining industry is attracting investment and justifying new projects by citing projected critical metals demand and framing itself as a key actor in the transition.

- Metal mining as a driver of socioenvironmental conflict offers a sense of the systemic and global nature of the social and ecological impacts of metal mining.

- Moving beyond extractivism offers a sense of possibility in suggesting different ways forward, by addressing both the material and political challenges to a postextractivist transition.

This report finds that:

- Current models project that as fossil fuels become less prominent in the generation of energy, metalintensive technologies will replace them. The assertion that economic growth can be decoupled, in absolute terms, from environmental and social impact is deeply flawed.

- Central to these models is the unquestioned acceptance that economic growth in the Global North will continue unchanged, and as such, will perpetuate global and local inequalities and drive the demand for energy, metals, minerals and biomass further beyond the already breached capacity of the biosphere.

- The assumption that economic growth is a valuable indicator of wellbeing must be challenged. Scarcity is the result of inequality, not a lack of productive capacity. Redistribution is the answer to both social and economic injustice and the threat that extractivism and climate breakdown pose.

- Reducing fossil fuel energy dependence on its own is not a sufficient response to the intersecting socio-ecological crises, the extractivist model as a whole must be challenged.

- There is a need to address the extractivist model because mineral, metal and biomass extraction threaten frontline communities and the interconnected ecologies that sustain life and wellbeing.

- This need is particularly urgent because the mining industry is driving a new greenwashing narrative by claiming that vast quantities of metals will be needed to meet the material demands of renewable energy technologies.

- This greenwashing narrative serves to obscure and justify the inherently harmful nature of extractivist mining. International financial institutions and sectors of civil society that have embraced these assumptions are complicit in the mining industry’s greenwashing efforts.

- Increased investment and political will for large-scale mineral and metal extraction is not an inevitable consequence of the transition, it is one of the fundamental contradictions within a vision of climate change mitigation which fails to understand extractivism as a model fundamentally rooted in injustice.

- Around the world, frontline communities are pushing back the expansion of extractivism and offering solutions to social and ecological injustice. But unfortunately, their voices, demands and visions are far too often absent in climate policy and campaigning spaces and agendas.

- Justice and equity need to be understood as cross-cutting issues that touch every aspect of the transition. These principles are fully compatible with ecological wellbeing and mutually enhance one another. Increasing access to energy, food and public services goes hand-in-hand with reducing excess consumption through processes of redistribution. The solutions are fundamentally social; technical fixes and increases in efficiency do not bring about justice or ecological wellbeing on their own.