This article will briefly introduce and explain how the Escazu agreement may positively impact the Right to Say No. To better understand it, we will start by explaining where it comes from, its unique characteristics, its aims, the rights it granted and its link with our campaign ‘The Right to Say No’ in Catapa vzw.

The Regional Agreement on Access to Information, Public Participation and Justice in Environmental Matters in Latin America and the Caribbean, also called the Escazú Agreement was adopted on 4 March 2018 and entered into force on 22 April 2021. Within the UN Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) with 24 Signatories States and 14 Parties among them (Colombia, Ecuador, and Bolivia).

“CIDH- ddhh indigenas Colombia _1039” by Comisión Interamericana de Derechos Humanos is licensed under CC BY 2.0

.

.

The Escazu agreement is quite unique for three reasons: first of all, it is the only legally binding agreement coming from the United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development (Rio +20); secondly, it is the region’s first treaty on environmental matters; and thirdly, it is the world’s first treaty to include provisions on human rights defenders in environmental matters.’

The main aim of the agreement is to fulfil the goals of principle 10 of the 1992 Rio Declaration on Environment and Development, which states that:

‘Environmental issues are best handled with participation of all concerned citizens at the relevant level. At the national level, each individual shall have appropriate access to information concerning the environment that is held by public authorities, including information on hazardous materials and activities in their communities, and the opportunity to participate in decision-making processes. States shall facilitate and encourage public awareness and participation by making information widely available. Effective access to judicial and administrative proceedings, including redress and remedy, shall be provided.’

In this manner, the agreement strives for ‘the right of present and future generations to live in a healthy environment and to sustainable development’.

How is it related to the Right to Say No?

The Right to Say No stands for ‘communities’ fundamental right to not only be involved in – and informed about the plans, but also, in cases of unsatisfying outcomes of negotiating processes, to finally say “No” to the proposals. This essential notion not only amplifies communities’ voices and puts them in a more equitable position, but also puts pressure on corporations to respect indigenous knowledge and customary law. The “Right to Say No” to mining is therefore also the right to say “Yes” to a self-determined living and gives communities a concrete instrument to come up with their own development model through grassroot processes and law from below.’

This right has been built upon the principle of Free Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC) which enables indigenous peoples to grant or not consent to projects that may affect them or their territories.

Aligning with this concept, The Escazu Agreement is a valuable regional legal mechanism to support the exercise of the Right to Say No in Latin America and the Caribbean, due to the recognition and protection of access rights it granted, such as the right of access to environmental information, the right of public participation in the environmental decision-making process, and the right of access to justice in environmental matters.

What do these rights entail in the agreement?

Right of access to environmental information

The right of access to environmental information comprises access to the relevant information of the projects following the principle of maximum disclosure, which means that people can request and receive information from competent authorities without having to prove any particular interest or reason, which will represent the opportunity for private individuals, ONGs, and associations to be informed in each of the negotiating stages of the mining projects enables them to act before the authorities make any definitive decision upon the lands.

It also entails the duty of the signatory parties of the Escazu Agreement to facilitate this access to environmental information for persons or groups in vulnerable situations through the implementation of procedures to assist and advise them in the preparation of their requests until obtaining a response to guarantee the exercise of this right under equal conditions. This means that the government shall provide the necessary assistance and legal advice to people who, given their particular situation, may not have the knowledge or financial resources to submit the requests on their own but want to take part in these of processes.

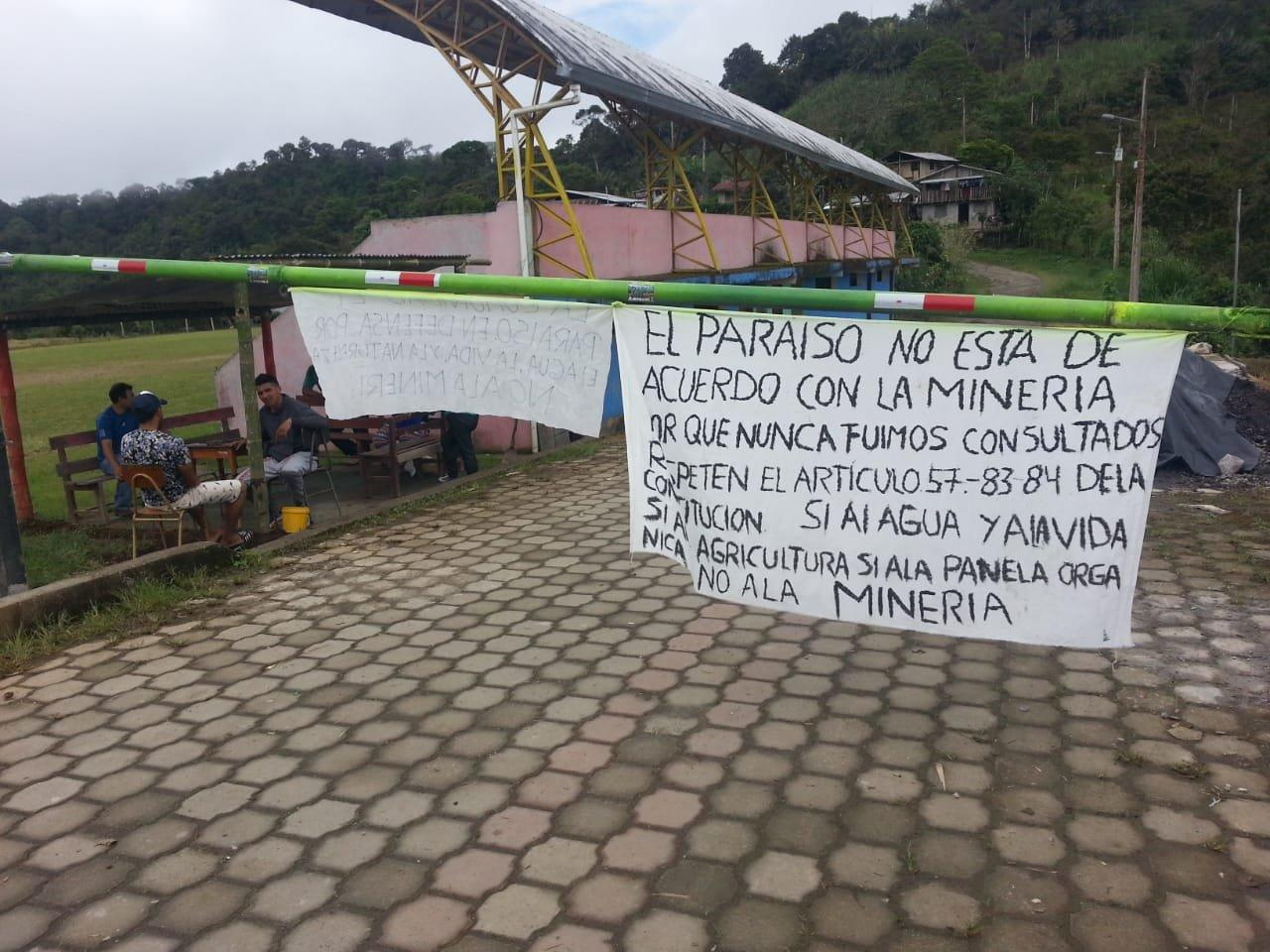

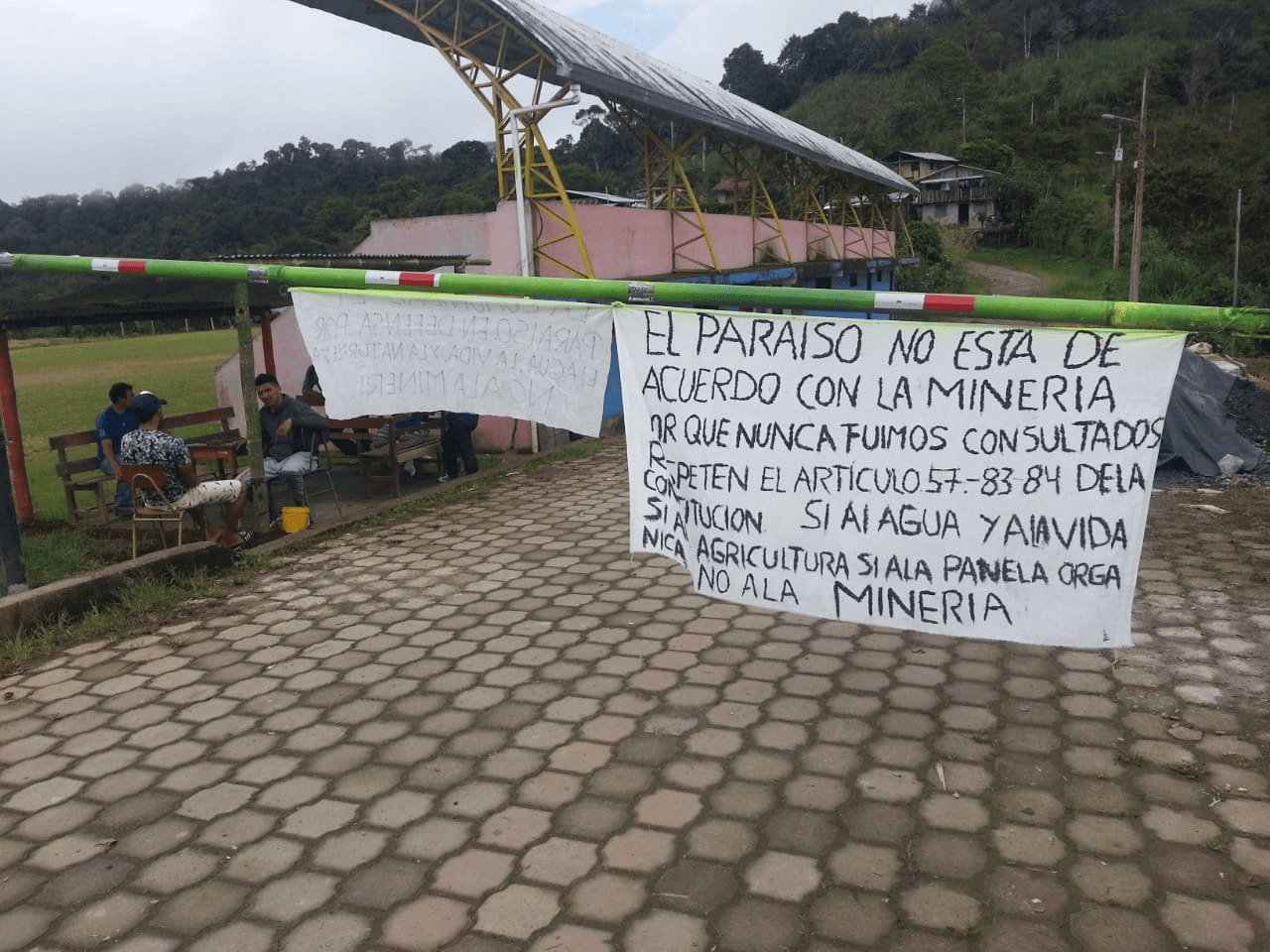

“No a la Mineria” by somos2013 is licensed under CC BY 2.0

“No a la Mineria” by somos2013 is licensed under CC BY 2.0

.

.

It also includes under which circumstances the states are allowed to refuse the information requested and the applicable conditions for delivering the information bringing transparency and clarity about the legal grounds, limits and exceptions to exercise this right. The Escazu agreement also asks parties for the designation of impartial institutions to oversee the compliance of the provisions and rules set forth therein. This right will represent an enormous change to the current procedures where most of the time environmental information is regularly denied to people or authorities, making it too complicated to be understood by people not involved in the projects.

Right of public participation

The right of public participation in the environmental decision-making process involves the creation of open and inclusive participation mechanisms following domestic and international normative frameworks, meant to include the public from the very early stages of the projects and activities in environmental matters such as processes to granting environmental permits, revisions, re-examinations or updates. Any aspect of public interest, such as land-use planning, policies, strategies, regulations, etc. And requires from the signatory parties the dissemination of the decisions taken and how the remarks of the public were considered to reach upon the decisions.

Thanks to the Escazu Agreement, from now on, the public has the right to oversee and be involved in the projects from the very beginning, which will represent no more ugly and unexpected surprises to the communities and society about the fate of their lands. From now on, their voices must be heard and considered, and the states will have to prove how the recommendations and decisions made by the public were included at the time of making the decisions.

Right of access to justice

The right of access to justice in environmental matters, demands from the signatory parties to adequate their domestic legislation with guarantees of respect to the principle of due process, implementing judicial and administrative mechanisms that allow the public to challenge and appeal any decision, action or omission that affect the exercise of the access rights or when any decision, act or omission may affect the environment or may represent a violation of the laws and regulations related to the environment.

As mentioned before, one of the agreement’s highlights is its provisions related to human rights defenders in environmental matters. Since it is the first binding agreement in the world that demands guarantees of safety and an enabling environment for persons, groups and organisations that work promoting and defending human rights in environmental matters.

In this aspect, the agreement calls for the implementation of adequate and effective measures to opportune intervene in the defence, protection and promotion of all the rights of human rights defenders in environmental matters, including ‘their right to life, personal integrity, freedom of opinion and expression, peaceful assembly and association, and free movement as well as their ability to exercise their access.’

Finally, the agreement encourages the implementation of its provisions through the creation and strengthening of the parties’ national capacities to take measures, meaning to train authorities, civil servants, judicial officials, national human rights institutions, jurists and the public in general in the access rights recognised by the agreement, and acknowledge the vital role that associations, organisations and groups play for raising public awareness in access rights.

“Mineria Amalfi 07” by Antropovisual is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

“Mineria Amalfi 07” by Antropovisual is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

.

.

What is the future of the Escazú Agreement?

Although the ratification process of this ambitious agreement has been slow, given the lack of political will by the signatory parties, the Escazú agreement represents a landmark for the exercise of the Right to Say No since it provides a regional legal background in Latin America and the Caribbean in recognition of access rights whereby communities, groups and individuals can say no to mining projects and propose alternatives to it.

The Escazú agreement has a long way ahead and many obstacles to surpass before becoming a solid milestone for protecting communities’ access rights, which it cannot do alone. Therefore, the work now is raising public awareness of it, promoting its ratification by more states and monitoring its implementation with the aim of equipping communities with more legal mechanisms to exercise their right to say no to the current destructive economic system and encourage the recognition of the access rights and promotes its ratification for those states are still pending to do it and monitor its implementation in those states which already ratified it.

In Catapa vzw, we want to continue promoting the Right to Say No to mining and The Right to Say Yes to a sustainable way of living where communities can determine and overwatch the decisions related to their territories. Therefore, we want to show our support for the ratification and implementation of the Escazu Agreement, given its shared values with our campaign RTSN, where our fight for a better future without mining continues until our voices are heard.

This article has been written by Catapista Laura Carvajal.

Bibliography

“

“