Lithium exploitation is drying out the world’s driest desert

*This article is a summary of a longer investigation project from Danwatch, published in collaboration with CATAPA and SETEM. More information at the end of the article.

The Acatama Desert in Chile, the world’s driest desert, is gradually losing its last water resources. Indigenous communities have been sounding the alarm for several years and are now being strengthened by scientific research and environmental organisations. Cause of this dehydration? Lithium mining.

Lithium is essential for the batteries in our phones, our computers and the explosive increase in the number of electric vehicles that are often seen as the key to a green energy transition. Chile, which has half of the world’s lithium reserves, has been declared the ‘Saudi Arabia of Lithium’ and almost all of its exports are currently extracted from the Atacama Desert, the driest place in the world. But extracting Atacama’s lithium means pumping up huge amounts of scarce water resources. Water resources that have enabled indigenous peoples and animals to survive in the desert for thousands of years.

According to researchers, extraction is already causing lasting damage to the area’s fragile ecosystems. In the Atacama and elsewhere in Chile, indigenous communities are now protesting against current and future plans for lithium extraction. Many communities claim that they were never consulted before the mining projects, although the Chilean authorities are obliged to do so under international treaties ratified by the Chilean state. The Danish research centre Danwatch can document that companies like Samsung, Panasonic, Apple, Tesla and BMW get batteries from companies that use Chilean lithium.

With the country’s incomparable lithium reserves and the increasing importance of the metal for the energy sector, Chile has occasionally been awarded the label ‘Saudi Arabia of Lithium’. Nearly 40 percent of the global supply comes from Chile over the past 20 years and, as Danwatch can reveal, it ends up in some of the most popular electronics and electric cars. The metal is one of the most popular products of the Chilean energy sector.

However, the Atacama’s indigenous communities were caught up in speed. Chile has signed ILO Convention 169, which obliges governments to consult indigenous people when major projects are carried out in their area. However, according to the people of Pai-Ote, they were not consulted before the lithium projects were presented in the media. “We found out from the press that an agreement had been made that allowed SQM to start lithium mining here. Nobody asked the Colla people if they wanted the mining on their territory,” says Ariel Leon, representative of the Colla community.

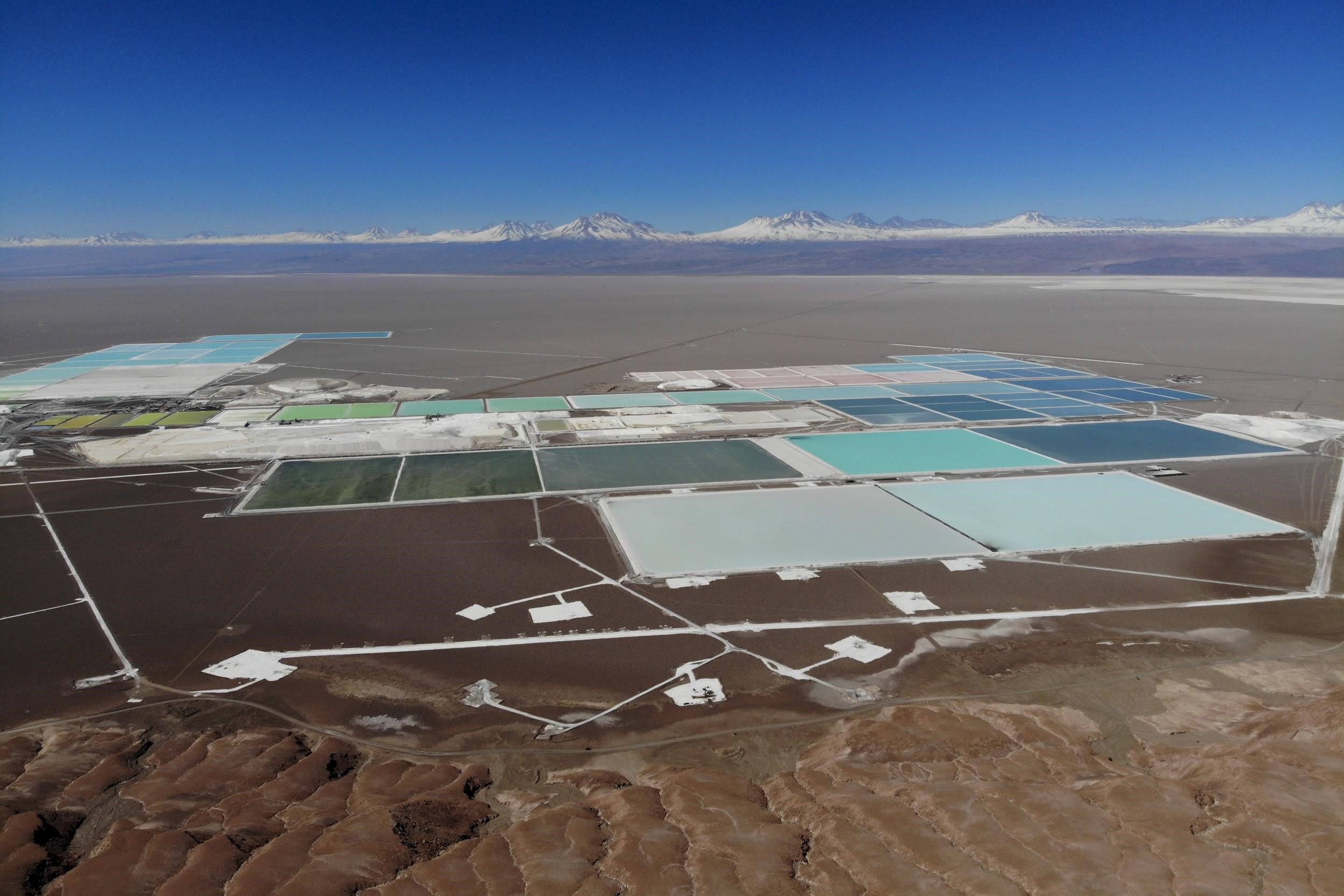

Chilean lithium can be extracted at low cost: miners pump lithium brine from a massive reservoir under the Atacama salt plain to huge puddles on the surface of the desert. The highest solar radiation in the world causes the water in the brine to evaporate quickly, causing the lithium to be scooped up together with other salts and minerals.

During this process, 95% of the extracted brine evaporates into the air. This accelerates the water scarcity in the Atacama, says Ingrid Garces, a professor of technology at the Chilean University of Antofagasta, who conducts research into salt pans. “In Chile, lithium mining is considered to be a normal form of mining, as if you were mining a hard rock. But this is not regular mining – it’s water extraction,” she says.

The two companies behind lithium mining in the Atacama, the Chilean Soc. Química & Minera de Chile (SQM) and the American Albemarle Corp. have permits to extract almost 2,000 litres of brine per second. In addition to the brine, lithium miners also extract significant amounts of fresh water along with the nearby copper mines. “The result is an impact on biodiversity in general. And that effect is already visible – the wetlands are drying out,” says Ingrid Garces.

Atacama’s indigenous communities have been sounding the alarm about water scarcity for years. According to the Atacama People’s Council, which represents 18 indigenous communities, rivers, lagoons and meadows have all declined in water over the past decade. However, the Chilean authorities have largely relied on the environmental impact assessments of the mining companies themselves. And, in general, these studies have not found any significant impact on water levels or the surrounding nature.

“For the locals, the change is very clear. They notice that there is less water for their animals, and they see how the rivers dry out. This anecdotal knowledge is not taken seriously by the companies or the state,” says Cristina Dorador, biologist and associate professor at the Chilean University of Antofagasta, who studies the microbial life in the Atacama.

In August 2019, an analysis of satellite images by the satellite analysis company SpaceKnow and the scientific journal Engineering & Technology came to a similar conclusion. Based on satellite images from the period 2015-2019, they saw a strong inverse relationship between the water level in the lithium ponds of SQM and the surrounding lagoons: “As the water level in the SQM ponds increased, the water level in the lagoons would drop”.

Ironically, the Atacama salt plain was once a large lake before it dried up thousands of years ago due to severe climate change. Scientists are studying the desert today as an example of what can happen to ecosystems elsewhere on the planet if global climate change becomes effective. But in an effort to mitigate rising temperatures with electric cars, industries are sucking away the little water left in the world’s driest desert with all the social and ecological impact as a consequence.

Companies are often greenwashing. This greenwashing narrative is based on the claim that a substantial increase in metal mining is necessary to meet the material needs of renewable energy technologies and associated infrastructure. However, the renewable energy sector will under no circumstances consume the majority of the metals’ annual production. Nevertheless, this narrative let mining companies sacrificing new sites to explore

Danwatch, SETEM and CATAPA did research to the impact of lithium exploitation in the framework of the European project: Make ICT Fair. This project wants to make the supply chain of electronics more visible and influence public buyers to ask their ICT suppliers, both mining companies and manufactures, to improve environmental and labour condition. Lithium, as one of the most important metal in the transition to green economies, became the focus of this article.

Danwatch has been to Chile to investigate the country’s growing lithium extraction industry. In the process, they have interviewed numerous scientists, companies, politicians and the people who live closest to the extraction sites. They have reviewed the mining companies’ impact studies as well as the few independent research papers on the topic. They especially base the investigation on a 2019 study on lithium mining in Chile by researchers from Arizona State University’s School of Sustainability.

The investigation is supported by the EU-funded project Make ICT Fair and published in collaboration with SETEM and CATAPA.

DEVICES DRAINING THE DESERT

Check all the articles from the investigation project below.

ARTICLE 4: There’s probably Chilean lithium behind the screen you’re reading this on.

ARTICLE 5: How much water is used to make the world’s batteries?

ARTICLE 7 / VIDEO: Watch the surreal lithium extraction landscapes from above.