A MATERIALS WAR: UKRAINE AND THE RACE FOR RESOURCES

Wars are both political and material. Hidden underneath Ukraine’s fertile land are vast amounts of resources that global powers desperately want. The risk of a resource grab sold to the public as “rebuilding Ukraine” is very real, write Robin Roels, Diego Marin and Nick Meynen.

Wars have been fought and lost for access to energy, be it in the form of resources such as fossil fuels, or control of strategic industries like metallurgy, or agricultural lands. For example, oil may not have been the reason for the Iraq war, but it sure was a reason, and a major one.

The hunger for Ukraine’s resources

To feed the motor of continuous economic expansion, countries need ever more resources. Ukraine is one of the world’s most resource-rich countries. The Donbas and Mariupol regions alone contain in ‘commercially viable quantities’, a large majority of the most used minerals and metals in today’s economies.

A part of the 3 to 11.5 trillion dollars worth of resources in Ukraine is now under Russian boots. This includes elements such as tantalum and niobium that are used for green(er) technologies as well as aviation, transportation and construction. As the amounts of elements like tantalum and niobium are state secrets, it is hard to estimate how much of it is now in Russian hands, but these materials are found in Donetsk and south of Zaporizhzhia, which are occupied by Putin’s invading army.

Russia’s destabilization of Ukraine positions it to achieve a high degree of leverage and control over a significant share of global commodities ranging from food to strategic minerals, write @robmuggah and Vadim Dryganov. https://t.co/pSeOtQ4SE9

— Foreign Policy (@ForeignPolicy) May 1, 2022

In a complete turn-around from the 1980s manufacturing exodus to Southern countries, the US and the EU are now promoting on-shoring or friend-shoring: the strategy to get resources from their own territories and those of allies. Eight months before the start of the war, in July 2021, European Commission Vice-President Maroš Šefčovič had launched a strategic partnership on raw materials with Ukraine, with the purpose of “achieving a closer integration of raw materials and batteries value chains”. Ukraine was supposed to become a car battery hub for the EU.

In recent years, Ukraine has been busily expanding investment in mining. UkraineInvest, the government investment promotion office, received more than 100 investment proposals from across Europe and North America of up to $10 billion to develop 24 major mineral locations.

EU, Ukraine sign ‘strategic partnership’ on raw materials https://t.co/NsiAHx7Xs9

— EURACTIV Energy & Environment (@eaGreenEU) July 13, 2021

For decades, the Global North has extracted materials from the Global South in an unfair manner, keeping the industry that adds most value in the North while leaving the South to deal with most social and environmental impacts. Today, with Europe’s influence in the Global South increasingly challenged by China, it seemed strategic for the EU to turn eyes to its eastern and south-eastern backyard, with Serbia standing out as the most recent example.

A reconstruction of the Ukrainian economy based on the EU’s objectives is likely to point in this direction, and make the country become a prime site for extraction and exploitation. However, the reconstruction of Ukraine must happen in a just way that respects planetary and social boundaries, as made clear by Andriy Andrusevych from Society and Environment, an Ukrainian member of the EEB.

🇺🇦 Our board member from Ukraine, Andriy Andrusevych @soc_env joined the annual conference with strong and moving words about the war and its impact.#EEB22 pic.twitter.com/19Dv4NMAN3

— EEB (@Green_Europe) June 17, 2022

There is no such thing as ‘green mining’

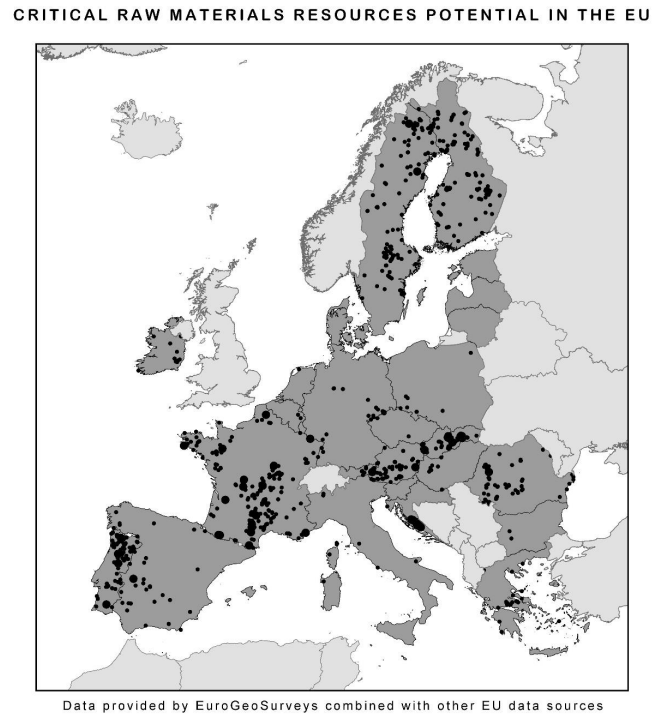

Green, environmentally friendly mining is just a myth that conceals a wide range of local environmental and social impacts – even when it serves the production of an electric car’s battery. Yet the EU’s response to the rising demand for metals and minerals to feed the twin digital and energy transitions has been to advocate for more mining within EU member states, as well as a renewed pursuit of raw materials diplomacy that will benefit Europe, but comes at a cost for the countries of extraction.

📈Europe's green and digital transitions are boosting metals and minerals demand

⛏We can keep digging for resources… or rethink the way we use them in the first place

💡Spoiler alert: there's no such thing as 'green mining', but there are better wayshttps://t.co/zOWSzlI57X

— EEB (@Green_Europe) October 13, 2021

As a consequence, not only Ukraine but also many countries within the EU risk falling victim to the priorities of the European economy’s growth-fueled machinery. On top of this, the need for metals for the green transition is co-opted to start many new mining projects for raw materials that we do not need in the first place, such as gold and iron. Suddenly, all mining projects are becoming “energy transition projects.”

The risk is real that the proposed solution actually creates a new problem, without solving the original one. So far, the green energy transition has been a green energy addition: fossil fuel energy consumption has been increasing, rather than decreasing. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), the worldwide growth in electricity demand has been slowing down in 2022. However, as long as the trend in energy demand remains positive, it will be impossible to satisfy Europe’s demand sustainably.

The path to peace and independence

The alternative to increasing our dependence on raw materials from other countries, is to need less of them in the first place. At the same time, the correlation between more material demands and more conflicts is very strong. A lot of our tensions with Russia would be solved if we needed less gas from them, something the European Commission is now actively working on. The same applies to raw materials.

This is clearly shown by the EEB’s LOCOMOTION project, which is improving an existing model that demonstrated that a transition from fossil fuels to renewable energy systems could drive a steep re-materialisation of the economy. In a ‘Green Growth’ scenario, even when moving 100% towards renewables and boosting recyclability, cumulated extraction demand would surpass the current levels of reserves for tellurium, indium, tin, silver and gallium by 2060. All of these are key for renewable energy systems.

LOCOMOTION research further shows that material availability may pose serious problems in the next decades, especially in the case of solar. Hence, it is imperative to reduce both material and energy demand as well as to focus on recycling and substitution of materials for less environmentally impactful ones. We will still need materials in the future, for building our renewable energy grid and batteries to store energy, but taking the aforementioned measures will reduce pressures for their extraction.

We are all going to lose the battle for existence if we do not rethink how we use energy and raw materials. Green growth is a myth that keeps countries at odds with each other in this race for resources to deplete. There is only one viable peace settlement for this underlying war: embracing the limits to the growth of our economies, energy, and material consumption by setting targets, applying truly circular strategies – sharing, reusing, repairing and recycling – combined with cutting resource consumption that does not contribute to our wellbeing.

Just as we have learned that we cannot keep burning fossil fuels, we now have to come to terms with the limits of how much we can dig up, in a fair and just way, within our planetary boundaries.

Continuing the race for resources without considering systemic and demand-side solutions is likely to cause ever more environmental harm, insecurity and conflict. The opposite would be resource justice: the fair and considered distribution of the Earth’s resources without depleting them.

Written by Catapistas Robin Roels and Diego Marin, and Nick Meynen (EEB). Article originally published in META (EEB). Photo taken by Alberto Vázquez Ruiz.