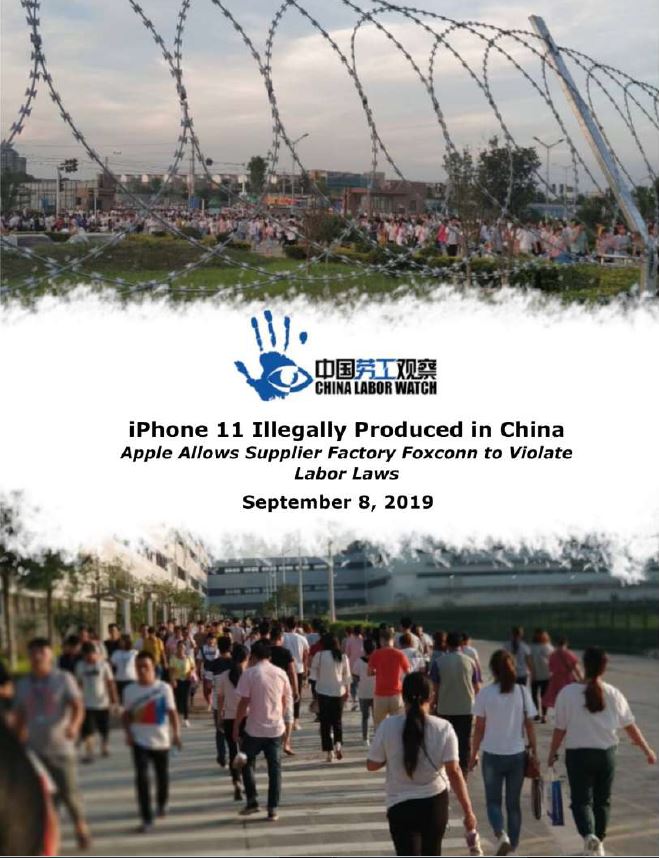

iPhone 11 Illegally Produced in China: Apple allows supplier factory Foxconn to violate labor laws

iPhone 11 Illegally Produced in China

Apple allows supplier factory Foxconn to violate labor laws

“Over the years, China Labor Watch has monitored the working conditions at several Foxconn facilities and investigations have revealed a string of labor rights violations. In this year’s report, several investigators were employed at the Zhengzhou Foxconn factory, and one of the investigators worked there for over four years. Because of the long investigation period, this report reveals many details about the working and living conditions at the Foxconn factory.”

Among others, some of the labor rights violations registered at Zhengzhou Foxconn by NGO China Labor Watch are the following:

- New workers have a probationary period of three months and if they wish to resign during this time, they must apply three days in advance.

- During peak season, regular workers’ resignations won’t be approved.

- After completing resignation procedures, factories will pay workers in around two weeks with no pay stub provided that month.

- Some dispatch workers failed to receive their promised bonuses from the dispatch company.

- The factory does not pay social insurance for the dispatched workers.

- In 2018, dispatch workers made up 55% of the workforce. Chinese labor law stipulates that dispatch workers must not exceed 10% of the workforce. In August 2019, around 50% of the workforce were dispatch workers.

- During peak production season, student workers must work overtime. However, according to regulations on student internships, students are not to work overtime or night shifts.

- Chinese labor law mandates that workers must not work more than 36 overtime hours a month. However, during the peak production seasons, workers at Zhengzhou Foxconn put in at least 100 overtime hours a month. There have been periods where workers have one rest day for every 13 days worked or even have only one rest day for a month.

- Workers have to receive approval not to work overtime. If workers do not receive approval and choose not to work overtime anyway, they will be admonished by the line manager and will not be working overtime in the future.

- If work is not completed by the time the shift ends, workers must work overtime and workers are not paid for this. If there are abnormalities at work, they must work overtime until the issue has been addressed, and work done during this time is also unpaid.

- Workers sometimes have to stay back for night meetings at work, and this time is unpaid.

- The factory does not provide workers with adequate personal protective equipment and workers do not receive any occupational health and safety training.

- The factory does not provide a single training class on fire safety and other relevant knowledge.

- The chairman of the labor union is always appointed by the factory, not elected by the workers, and the chairman is always the department leader or manager.

- The factory does not report work injuries.

- Verbal abuse is common at the factory.

- The factory recruits student workers through dispatch companies, as student workers sent by schools are subject to many restrictions.

- The factory violates the “The Administrative Provisions on the Internships of Vocational School Students” which stipulates that student workers cannot be recruited by agencies or dispatch companies but only schools.

Read the full report here: Zhengzhou Foxconn