The End of Naïve Europe,The Rise of Green Imperialism

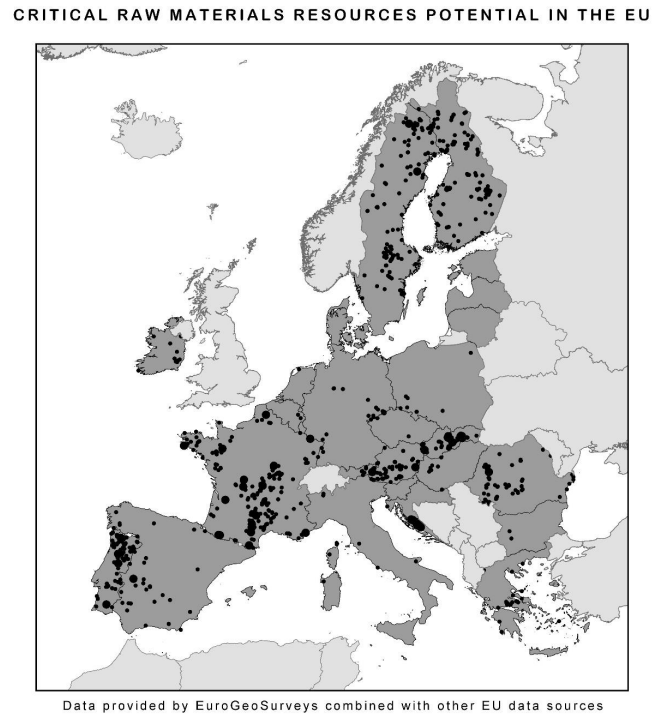

Image: CRM deposits EU-27 (2020). Source: European Commission’s M(2020) 474 final.

ARTICLE:

Re-published from: Vázquez Ruiz, A. 2020. “Op-Ed: The End of Naïve Europe, The Rise of Green Imperialism.” Commodity Frontiers 1: 56-59. doi:10.18174/cf.2020a17975.

The End of Naïve Europe,The Rise of Green Imperialism

Author: Alberto Vázquez Ruiz

On 29 September 2020, the European Commission officially launched the European Raw Materials Alliance (ERMA), a publicly supported “industrial alliance dedicated to securing a sustainable supply of raw materials in Europe”. In other words, firing the starting pistol of public funding for the race to explore and extract mineral deposits outside the European Union and especially within its borders.

Until now, the EU had only been financing mining and metallurgical private companies under the pretext of technological innovation and market competition. Since the launch of Horizon 2020 in 2014, the Commission has been assembling the institutional tools (e.g. EIT Raw Materials, the Partnership Instrument) allowing to finance private technology developments inside the EU for exploration, exploitation and metallurgy. Horizon 2020 is finishing this year, but the instruments created remain and the technological excuse seems no longer needed.

“The era of a naïve Europe that solely relies on soft power is behind us”. With these words, Commissioner for the Internal Market, Thierry Breton, announced earlier this month the “EU action plan for critical raw materials”, which is the EC’s strategy to face the consequences of the commercial war between the USA and China and to encourage EU nation states to focus on raw materials as part of a post-COVID19 ‘green’ recovery plan.

The pandemia has indeed created the perfect momentum to call for support for this industry. However, resource extraction and its processing together represent 90% of biodiversity loss and water stress in the world. Bad news, as many experts have already pointed to the relation between the pandemia and biodiversity loss.

It is impossible for the EC to ignore last year’s report by the International Resources Panel (UNEP), which clearly warned humanity that metal extraction and production has doubled health and climate change impacts from 2000 to 2015 solely. And today, mining and metallurgy are representing already 20% of all health impacts from air pollution and more than a quarter of global carbon emissions. So why is the Commission actually making this change of course?

The shift in its position has been justified as the “access to resources is a strategic security question for making the green and digital transformations a success”. Although the Commission claims to share the widespread will to combat climate change and to leave no person and no place behind in the process, the Commission also openly calls for an increased mining boom which will reinforce the pressing systemic problem facing people and planet.

While green technologies are based on energy sources which are renewable, their machines are not. Electricity generation based on solar, wind, tidal… generators rely on metals (many metals if you consider off-grid technologies). The planned transition without socio-economic restructuring towards schemes that push for drastic reduction in consumption of energy, will just move us from an energy matrix based on the extraction and combustion of fossil fuels towards a loop of increasing extraction and processing of metals for the manufacturing of metal-based solutions.

It could be argued that a society based on metal-based technologies is a sustainable scenario because we would be able to recycle these elements in the future, but the reality is very far from this. The IRP-UNEP also warned us that “only 18 metals have recycling rates higher than 50%”. For the rare earths elements (REEs) needed in most green energy technologies, the recycling rate reaches just 1%. What will happen in 30 years when the energy machines are already obsolete and fossil fuels are no longer efficient to be extracted? Mining, metallurgy and manufacturing industries are the biggest energy consumers. “What is happening today is nothing less than a massive PR campaign to sell the idea that mining is not only necessary but it can also be sustainable,” said Nick Meynen, Policy officer at the European Environmental Bureau (EEB).

While the EC’s Action Plan does recognise the need for improving recycling rates and the importance of reinforcing the circular economy, it lacks a coherent set of proposals that could tackle the reasons behind the low recycling rates and the slow implementation of a circular economy. There are no regulations for recyclability (yes, but more importantly there are no restrictions on production, so materials can be mixed in a way which make the products poorly recyclable, but cheaper – it is not a end-of-use technological issue), repairability (modularity in products and regulations to end the monopoly on spare parts production), reusability (plans on how to proceed with older machines).

Breton recognises that the “post-war world architecture is faltering”, but the proposed treatment seems to be confusing the disease and the cure. His decision will accelerate the process, shaking the social foundations of our civilization even harder, instead of rebuilding our system by attacking the true causes of our current crisis. It can be seen both as a symptom of political negligence or as a part of a more complex agenda towards green imperialism.

Europe has expressed its aim to become the green energy superpower. However, the amount of minerals that the EC considers necessary for the future transition is extreme and the global metal demand already increased by 87% from 1980 to 2008. “Critical raw materials” (a techno-political rebranding of the elements the EC considers necessary today) are increasingly required for batteries in electric vehicles and off-grid generation and storage, among others. There is no way of getting that huge amount of resources without pushing social peace to its limits – also inside the EU.

“The transition to a low-carbon economy – and the minerals and metals required to make that shift – could affect fragility, conflict and violence dynamics in mineral-rich states”, reported the International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD) in 2018. A similar and simpler analysis was made by the EEB that year: “More mining leads to more fighting”. This is the reality that local communities and civil societies organisations are facing all around the world. Global Witness has even accounted mining as the main sector responsible for the killing of land and environmental defenders across the globe. This reality has been commonly associated with the Global South. Further evidence that the due diligence voluntary process, which is supported by the EU to guarantee responsible sourcing of metals, is far from useful in avoiding human rights violations.

Now, in the middle of the coronavirus crisis, Europe seeks to compensate its weaker commercial share, and to reinforce the aim to secure its supply, with insourcing. Breton mentions that the Action Plan seeks to “protect our democracies against the menace of disinformation”, but at the same time points out that the major barrier to develop the insourcing is a lack of “public acceptance” in the European society to allow new mining projects to start operating. Therefore, several EC financed research projects have been looking for increasing “public acceptance” for this sector in local communities across the Union affected by proposed and/or operating extractive projects.

There is still no democratic capacity to decide by local communities nor their municipalities on the mining projects that will drastically change their land and very possibly leave tonnes of mining waste landfilled in their towns waiting. The discourse of the EC is that there is a lack of understanding of the mining sector by local communities and that there is a need to educate the European society on the current reality of the mining sector (a false mantra by the sector is that the environmental issues of mining and metallurgy are a matter of the past). This discourse which mixes the real needs of our planet with the demand for resources caused by the Commission’s plans for an ominous EU Green Deal will lead down the path where destruction of the environment, land and societal configurations, is forced through for Europe’s future.

“By building, today, the foundations of tomorrow’s autonomy, our Continent has the opportunity to establish a set of rules, infrastructures and technologies that will make it a powerful Europe, without ostracism or discrimination”, states Breton. This sentence provides an insight into the future the Commission is implementing in Europe. A “powerful Europe” directed by the few privileged ones living in the “civilized world” of Europe’s main cities enjoying access to green energy, but an inequality nightmare for local communities worldwide which will be affected by the increasing environmental, social and political issues on which the Green Empire will rely. To prevent this upcoming reality, today many organisations state “We can’t mine our way out of the climate crisis”.

You can find more articles from the Commodity Frontiers journal this op-ed was published in, here.

Profile

Alberto Vázquez Ruiz holds a MSc. in Conflict and Development (UGent, Belgium) and is specialized in topics related to mining and electronics. Since May 2018 he has been Project Coordinator at CATAPA (Belgium), researching on metal supply chains, on socio-environmental impacts of mining operations on local communities and on extractive waste in the EU.