Chile is recognised as the poster-child of neoliberalism, with a strong mandate of privatisation on any capital-rich resource. A clear example of this mandate can be seen in extractivist projects, particularly mining and hydroelectric projects. As Chile’s economy grows, thanks to a global addiction to raw minerals, a sinister struggle underlies the country’s giant mining industry: water rights. And no, such rights are not found to trickle down from the private mining firms to the nation’s discriminated citizens.

The Maipo River Basin

Santiago de Chile, home to 7 million people, is a sprawling metropolitan jungle gripped to the roots of the Andes mountains. The Andes give the city not only a backdrop of formidable beautiful, they are also the source of the country’s most important water source: the Maipo river. The Maipo river basin runs 60km south of Santiago’s metropolitan region, supplying 90% of the city’s urban and residential water as well as 70% of total irrigation water (Baeur, 2016).

The significance of the river basin, also considered Santiago’s ‘green lung’, in providing life to the city and surrounding territories is undeniable, and its place in sustaining future generations translates its existence into a human and environmental right. Nevertheless, the Maipo river basin has become victim to an activity that threatens the supply of water to the citizens of the greater metropolitan region, one whose objective is to provide energy for Chile’s most lucrative industry: mining.

Copper: red gold

Copper mining is one of Chile’s most important economic activities, with 29% of global stock found in the country. Chile prides itself in being the number one producer of the red metal, for obvious reasons: Copper, and other precious metals, have made Chile the wealthiest country in Latin America (in economic terms). In short, copper is a resource which has infiltrated into the national fibre of Chile and the result is a heavily politicised and exploitative extractive industry. Mining is championed as the most attractive model for economic development and prosperity in Chile, and indeed, it can be argued that this economic model has given citizens a quality of life much sought after by neighbouring nations. But, this economic and material wealth has come at an alarming social and environmental cost.

Alto Maipo: an unnecessary project

50km southeast of Santiago, in the Cajon del Maipo region, the Alto Maipo Hydropower Project (PHAM) has become one of the biggest environmental struggles in the country’s history. The health of the Maipo river basin is under direct threat from two large-scale run of the river (ROR) hydroelectric projects which use the natural flow of a river to generate energy, avoiding the construction of a dam. With well-known tragedies of collapsing Dams, particularly jarring being the recent collapse of Brumadinho tailings dam in Brazil, a decision to avoid constructing a Dam may appear positive. The opposite is true.

Beginning in 2007, the Alto Maipo project has re-routed 100km of the Maipo river, bringing the flow of the river underground into artificial tunnels. The project, 68% complete, threatens environmental and social devastation for the citizens and ecological life of Cajon del Maipo depending on the rivers as a source of water. Further controversy underlying Alto Maipo is its proposed utility. Initially promoted as a public good to generate clean electricity and drive down energy costs, the majority of the generated energy will be supplied to Los Pelambres copper mine, the 5th largest in the world.

The Chilean mining subsidiary of U.S. company AES Gener, owner of Alto Maipo, won funding for the hydroelectric project from international development banks such as The World Bank’s International Finance Corporation (IFC) and the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB). The project was proposed as a clean source of energy with minimal environmental impact. This claim contrasts starkly with facts outlined by the Centre for International Environmental Law:

- Dramatic limitations on water access;

- 60% reduction in potable water; 70% reduction in irrigation water

- Significant erosion;

- Desertification;

- Impacts on protected areas and tourism;

- Human rights at risk.

Additionally, recent studies have shown that the construction of Alto Maipo has released heavy metals such as arsenic, lead and manganese into the water table to carcinogenic levels.

Coordinadora Ciudadana No Alto Maipo: a civil uprising

The scale of negative impacts is indisputable. The communities facing a future of water scarcity and environmental degradation have mobilised to create the Coordinadora Ciudadana No Alto Maipo, a campaign led by Marcela Mella Ortiz, its compelling and dynamic spokeswoman. No Alto Maipo is a response to a state-backed economic model which clashes relentlessly with citizens fighting to protect human and environmental rights. The dispossession of land is a common thread through the fabric of marginalized Latin America, yet the case of Alto Maipo is not one of geographic displacement; rather it is a displacement from our most indispensable resource: Water.

The controversy and societal backlash against Alto Maipo has remained present since its inception in 2007. Described by Mella Ortiz as an ‘unviable project from the very beginning’, the cost of the project now far exceeds initial investments ($600 million – $3 billion), reflecting the poor development plans of AES Gener. In 2017, Antofagasta, Chile’s largest mining company, removed its 40% share in Alto Maipo due to continuous budget increases. Further controversy surrounding the project stems from the numerous irregularities in the environmental impact assessments of the site. This rings resounding environmental alarm bells, coupled with bells of corruption and political playhouse tactics.

For more than 10 years, strings of sanctions and legal proceedings have followed AES Gener. Construction works have been suspended through judicial order, as the project expanded beyond the area outlined within the environmental impact assessment results.

Currently, the Compliance Advisor Ombudsman (CAO), an independent accountability mechanism which reviews private finance provided by the World Bank Group, is carrying out investigations into complaints that the environmental and social impacts of the hydroelectric project will cause irreversible damage to the health of communities and ecosystems along the Maipo river basin, including negative impacts on the Chilean economy.

The struggle for water rights: a familiar story

Civil society unrest surrounding water rights is an all-too-familiar story in Chile, the Mauro tailings dam of Caimanes being an emblematic case. The Caimanes case has grown into a 20 year struggle, one marked by displacements, criminalisation of leading activists and strategic divisions within the community orchestrated by Antofagasta mining company. This struggle has been described as a contention in a territory that “lacks political opportunities and resources”, a description which echoes the Alto Maipo case.

The Caimanes community has suffered from severe water loss as a direct result of the tailings dam, one built specifically to collect toxic waste from Los Pelambres copper mine. Understandably, the citizens of Cajon del Maipo and Santiago de Chile do not want to face similar levels of exploitation.

With aspirations by AES Gener to complete Alto Maipo by 2020, communities living along the construction lines are already suffering the impacts of such intensive extractivism. The project has been described as a ‘sickness’ and one that has drawn deep divisions between small communities.

Chile is a country with one the highest potentials for renewable energy production, so why are the government and private entities continuing along a path of such callous exploitation? Mankind’s addiction to mineral resources is on a course of acceleration, with OECD figures stating that consumption of global minerals is set to double by 2060. As such, the efforts of civil society groups like No Alto Maipo play a vital role in sustaining future livelihoods in Chile, but multilateral agreements and policies must be forged between civil society, government and private entities to achieve a sustainable future.

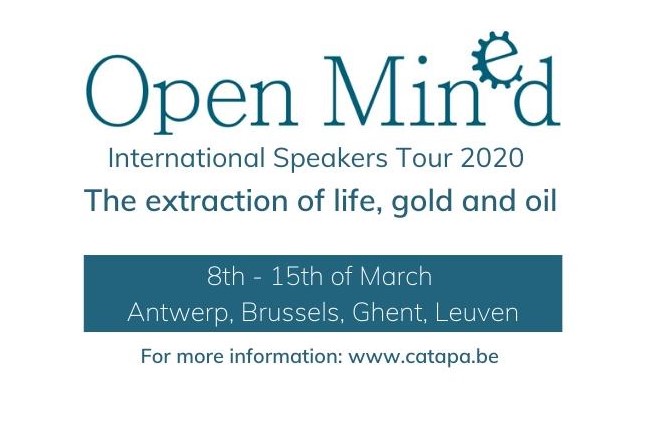

Despite the sanctions, suspensions and thousand-fold civil unrest, works have once again commenced on the project, with the 2020 completion goal in sight. Nevertheless, the work of No Alto Maipo and thousands of Chilean citizens is not over. To keep up-to-date with the activities of No Alto Maipo visit their website, Facebook and Twitter. Spokeswoman Marcela Mella Otriz will visit Belguim for the Open Min(e)d festival 10-17 March 2019. A full overview of her lectures and workshops in Ghent, Antwerp, Brussels and Leuven can be viewed here.