Neo-extractivism and repression of social protest in Bolivia

Neo-extractivism and repression of social protest in Bolivia

Bolivian Altiplano

We are looking out over a gigantic dry salt pan. Boats are lying upside-down on the cracks in the salty soil. In the surrounding villages, fishermen unable to do their regular jobs are forced to cultivate quinoa or raise animals in an environment that’s far from ideal for these pursuits. The Uru Murato are not used to agriculture, but when Lake Poopó dried up they lost not only their livelihood, but above all a foundation of their identity. A significant part of the population left in search for a new life in the city or even abroad, searching for a new job sometimes hundreds of kilometres away from their original homes.

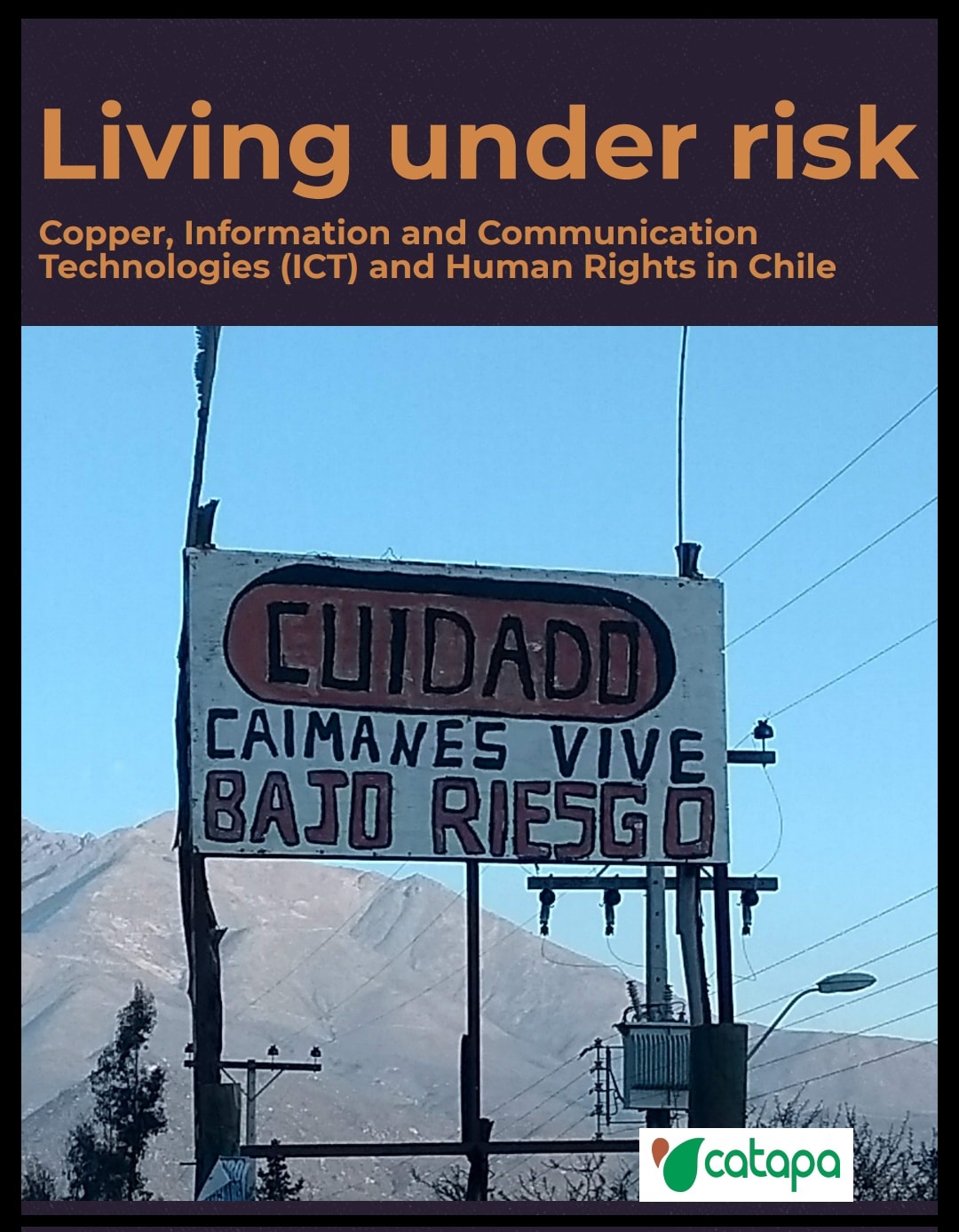

The Bolivian government identifies “climate change” as the main culprit, blaming CO2-emitting industrial nations and neighbouring countries that waste water. The accusations are not unfounded, but ignore a significant part of reality. Walking upstream along the Desaguadero, the stream that takes (or took) the water from Lake Titicaca to Lakes Uru Uru and Poopó, you inevitably encounter another element that contributed to the drying up of the latter: mining, with some 350 sites of various types and sizes scattered about the area around the river. There are a number of small and larger cooperative mines, as well as some large-scale projects owned by multinationals or the state. All have an irreversible impact on the area and its residents.

A persistent extractivist growth model

Mining is deeply interwoven with Bolivian politics and society, which explains the complexity of current conflicts in the sector. Metals were mined even before the Spanish colonists used them to fill their treasury. The appeal of the rich Bolivian soil to foreign investors has only grown since then. Despite regained control over its own natural resources through independence in 1825, nationalisations in the mining sector in the 1950s and the “proceso de cambio” (process of change) of current president Evo Morales, the Bolivian population experiences little structural difference. National development and sovereignty strategies remain, contradictorily enough, consistently based on the extraction and export of primary raw materials as one of the main pillars. Additionally, the new mining law of 2014, which replaced the one of 1997, appears to have been directed by mining cooperatives and (international) private companies, and continues the privatisation trend of the 1980s and 1990s.

Back to Oruro

With favourable tax regimes and limited restrictions, Bolivia then opened its gates wide to multinational companies that remain present to this day. The Bolivian state’s share in these companies often evolved from small to even smaller. One product of this is Kori Kollo, an open-pit gold mine on the banks of the Desaguadero river that extracts the precious metal using cyanide. The mine is no longer active (the huge crater was filled with water from the river) and the largest shareholder, Newmont, sold its shares back in 2009. However, the mine’s negative consequences for the environment and the population continue to be felt, not least because of its significant contribution to the drying up of Lake Poopó.

State mine Huanuni, located in the river basin of the same Desaguadero river, is not doing much better. Ore waste is being discharged directly into the river, causing acidification and high concentrations of heavy metals in the river and groundwater. Surrounding land is flooded with sediment and marked by sand deposits, making agriculture and animal husbandry virtually impossible.

These are only two (larger ones) of the countless mining sites that populate and pollute the Bolivian Altiplano. Control – by both tax authorities and environmental experts – is minimal, a framework and measures to protect the environment are virtually absent, and people continue to wait (with some disbelief) for the promised prosperity that the revenues from the sector would provide.

Social protest, attempts at cracking it and paper answers

Local residents have been experiencing the impact of mining activities in the area for decades. The population is increasingly aware of this and insists on its right to be heard, and questions central government decisions, in this case on private capital and the use of land and water. The 80 communities from the river basin and around Lakes Uru Uru and Poopó, which in 2006 united in CORIDUP – Coordinadora and Defensa de la Cuenca del Río Desaguadero, los lagos Uru Uru y Poopó, fought the government and multinationals for fair compensation and measures against further pollution, and to prevent further human rights violations.

They are assisted in this by CEPA, an NGO based in the nearby city of Oruro, which provides information flow and technical assistance, and raises visibility and lobbying to the regional, national and even international level.

A confrontation that is inevitably accompanied by intimidation. This conflict, which primarily relates to directly perceptible consequences of human interventions in the natural environment, is more broadly about democracy, about whose rights and voice count most in political-economic decision-making, and about various possible development models and their impact. In this discussion, unanimity within the various parties is a pipe dream, and polarisation is the central government’s preferred strategy to suppress protest. (Sounds familiar?)

The population’s unrelenting struggle has resulted in some responses though, albeit mostly on paper. Since 2002 Lakes Poopó and Uru Uru are Ramsar sites, internationally protected wetlands. From 2009 to 2012 an inadequate audit was carried out to measure the impact of the Kori Kollo mine. The area around the Desaguadero river basin was declared a disaster area in 2009, with a step-by-step plan to build a waste collection basin and a new processing plant to drastically reduce waste discharge from the Huanuni mine. Ten years on, neither basin nor plant are operative yet. Meanwhile, the Desaguadero river remains the ore waste bin.

Source: Historic mining site of Rio Tinto (Huelva, Spain) by Alberto Vázquez Ruiz

Source: Historic mining site of Rio Tinto (Huelva, Spain) by Alberto Vázquez Ruiz Source:

Source:  Source: Ecologistas en Acción Sevilla (Spain).

Source: Ecologistas en Acción Sevilla (Spain). Source: Image from the main

Source: Image from the main

25 January 2018

25 January 2018