Linking the Bolivian minerals to the European Industry

Executive Summary:

Linking the Bolivian Minerals to the European Industry

The Executive Summary is also available in Spanish and Dutch.

Introduction

Although indium might be a rare metal, it is not rare at all in your daily life. No smartphone can be produced without its use. Flatscreens, touchscreens, LED lights, photovoltaic panels and even the high efficiency glass of the windows in your house can contain this element.

Indium is a metal that has grown in importance since the 21st century. Lots of new technologies are based on its use, as it has the particular property of being transparent in thin coatings and still acting as an excellent conductor.

The source of this raw material is not always easy to track. The indium market is very opaque. This Executive Summary is part of a fact-finding mission by the European Union project ‘Make ICT Fair’. It tries to reveal a considerable part of the supply chain of indium by starting its research in the very beginning of the chain: a few mining cooperatives on the Bolivian highlands extracting silver-lead-zinc polymetallic ore; and it traces the supply chain beyond, feeding the European industry.

Supply Chain Summary:

- It is remarkable that official Bolivian data registers the export of indium as zero (MMM, 2019). This implies that neither the Bolivian miners nor the Bolivian state is paid for the extraction of this metal, indispensable for the technology of the 21th century.

- Bolivia is estimated as the 5th largest extractor of indium worldwide (Zapata, 2018).

- Bolivian silver-lead-zinc ores contain valuable concentrations of indium.

- A first concentration of the zinc ore from the remaining rock is in some cases done by the mining cooperatives themselves or, if the cooperatives do not have the necessary equipment, it might be done by local traders.

- On an individual level or collectively with all members of the cooperative, the minerals are sold to local traders. Based on the analysis carried out on behalf of the local trader at the moment of sale, the miners are paid for their materials.

- The local traders then further supply some of the largest commodity traders in the world. The minerals from different suppliers can be mixed to provide the concentrations required by the international traders who manage the purchase contracts and set up the conditions of sale.

- Bolivian actors have no control over the treatment charges (TC) applied, which are set by a small international oligopoly of zinc refiners and commodity traders. No smelting of zinc ore takes place in Bolivia itself despite the completion of a metallurgical plant for refining these concentrates in 2013.

- After almost 500 kilometers of transport by truck, the freight arrives at Chilean ports.

- 13.000 kilometers by sea transport brings part of the exported concentrates to the port of Antwerp, Belgium.

- On average every year 150.000 tonnes of Bolivian zinc ore arrives at the Port of Antwerp (Eurostat, 2013-2019).

- The Bolivian zinc ores rich in indium are very likely processed in Auby (owned and operated by Nyrstar), where also indium is being refined.

- Umicore refines rare metals in Belgium at its Hoboken and Olen metallurgical plants (both in Belgium – the company also operates in other countries).

- Umicore bases its production processes on secondary sourcing, which consist of recycling or slag from other refiners, such as Nyrstar. It means that the waste from primary materials processed by other smelters are further processed at Umicore’s installations.

- The Hoboken based copper smelter, lead blast furnace and lead refinery perform the extraction of metals such as indium, selenium and tellurium. Also the Bolivian silver and lead can be further refined by the Hoboken complex.

- In 2018, the metallic indium and indium powders produced in France (Auby, Nyrstar) and Belgium (Hoboken, Umicore) were mainly exported to the United States of America, Japan and South Korea (Eurostat, 2020 – see Figure 11). Both countries represent 85% of the European Union export on indium. The articles of indium produced in Germany (where Umicore also has production facilities) are mainly exported to China.

- It is still very challenging to recover the indium from the recycling of the end products. It is estimated that only 1% of indium is recycled worldwide from end of product waste (UNEP, 2013) and inside the EU the rate for End-of-life Recycling was recently reported at 0% (EC, 2020).

- The production of indium in Belgium for the year 2018 was estimated at 22 tonnes (USGS, 2020). The export data of unwrought indium and indium powder equals 16 tonnes for 2018 (Eurostat, 2020).

- Since Nyrstar was taken over by Trafigura Group, a prominent international commodity trader, is it challenging to track exactly where the flow of indium from the Auby smelter (in France) goes to. Two companies in France produce intermediary products of indium.

- In general flat-panel displays are by far the most frequent application for indium, making up for 60% of its end-use.

Conclusion:

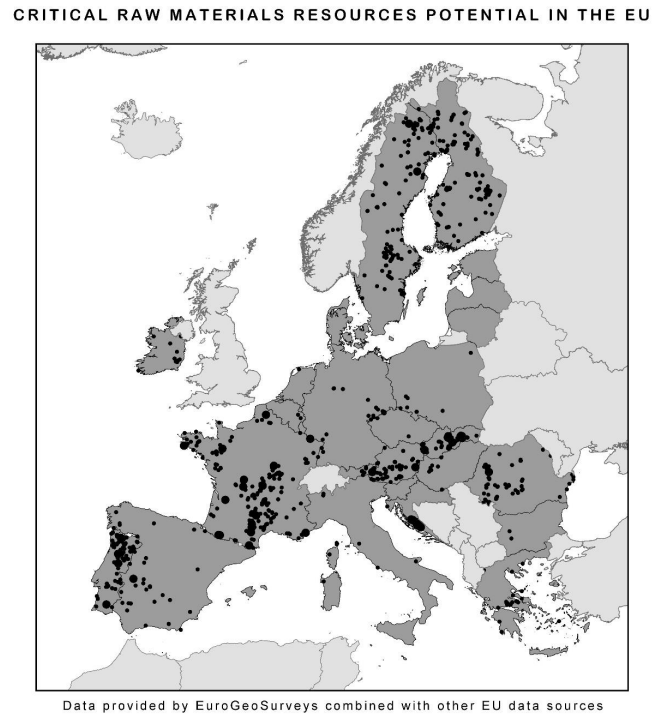

The EU’s Due Diligence framework is not working and will not work because it lacks four key components, that are necessary in order to avoid the ongoing human rights violations and environmental damage:

- It is not comprehensive; the EU’s Due Diligence framework lacks detailed information that can allow a standardised or homogenous way for its implementation (e.g., What is the list of requirements to decide if the case studied is in a CHARAs?).

- There is no transparency; there is no mandatory, defined structure for the companies to collect the data and make it accessible to the public so anyone can check its veracity.

- There is no accountability towards workers and communities, there is no way for other involved local actors to add more information about the local mining or metallurgical site besides the company itself.

- There is no governing body; no institutions have the mandate to take decisions on Due Diligence, nobody is able to monitor its implementation, no one can enforce or request anything about it.

Minor metals like indium, which are increasingly needed in the ICT industry, are extracted mainly as a by-product of the processing of ores rich in base metals such as zinc, lead and copper. In order to understand and track the supply chain of these scarce metals, it is necessary to start working from the extraction sites.

Taking into account the complexity and opacity in the industrial sectors, the existing approach based on the tracking of supply chains from the consumer end-products cannot reach the original sources of the raw materials being used. Therefore, it is neglecting the problems occurring in the first stages of the supply chain.

Recommendations:

There are few smelters and refining facilities in the world that have the technical know-how and metallurgical capacity to recover these metals. Therefore, a fairer and responsible supply chain would be today already possible if sufficient efforts were being made in the setting up of obligatory monitoring frameworks between the competent public institutions (at national and supranational levels) and the very few refiners and commodity traders dominating the market. The establishment of monitored supply chains is necessary if end-product consumers – whether from the public sector or the private – want to stop human rights violations, and prevent increasing environmental damage in the early stages of metal supply chains

The Bolivian State needs international transparency and supportive tracking systems in order to enforce its own legislation to tax minerals rich in indium – and other valuable rare metals it may be exporting – that currently leave Bolivian borders without any financial contribution. Without royalties for their minerals, the Bolivian Administration will hardly be able to independently afford the costs of the social and environmental services that mining activities cause in the short and long terms. This socio-environmental debt shouldn’t be left in the Bolivian hands alone, but corporations profiting from these minerals have to contribute to the mitigation and remediation of the ongoing human rights violations and environmental pollution included in the minerals they purchase, process and sell.

In summary, these are the authors key recommendations:

-

- The creation of a fair supply chain is urgent and needs the collaboration between public bodies that can legislate and enforce the law, international monitoring institutions that can report on the supply chains and community-based organisations that can give local information to contrast the data provided by the companies.

- Traders that cannot guarantee transparency on how the production of metals meets human rights and environmental standards, should not be able to sell in the international market, especially not EU companies. But first we need a legal structure to collect, access and monitor that information.

- Tax contribution by the companies exporting indium-rich minerals should be reported to and requested by the Bolivian state.

- The refining process of zinc and indium should be taking place in Bolivia to generate the added value locally and to cover the costs of remediating the environmental damage of the mining activities. It would also avoid the negative effects of the global transport of heavy mineral concentrates.

- Bolivia should implement the mitigation of its historical tailings at sites rented to cooperatives and enforce the treatment of wastewater from acid drainage. The Government has to ensure access to water as a fundamental right; water for domestic and agricultural use should always be prioritised over extractive and industrial activities.

The current situation also gives the large companies involved the ability to make a real difference through their sourcing process, by taking responsibility along their supply chain and by being transparent with their customers.

ICT products are the result of many actors throughout a long and complex mix of supply chains in several countries. Therefore, governments need to implement an appropriate global framework that can track this complexity and stop environmental damage and human rights violations wherever they occur. However, industrial efforts will still be required to drive the necessary change towards fair and responsible metal(s) production.

Read the Research in full here.

This article is part of the European Commission funded project “Make ICT Fair – Reforming Manufacture & Minerals Supply Chains through Policy, Finance & Public Procurement”.

CATAPA is one of its 11 co-applicants, which also include the University of Edinburgh (UK), Electronics Watch, Südwind (Austria), People and Planet (UK), SETEM Catalunya (Spain) and Swedwatch (Sweden), among others. The project aims to mobilise EU citizens, decision makers & ICT purchasers/procurers working in the EU Public Sector to improve the conditions of workers & communities along the ICT sector.

Send an email to communication@catapa.be introducing yourself.

Send an email to communication@catapa.be introducing yourself.