Deep Sea Mining: How Belgium is Sinking to the Bottom

WEBINAR & TRAINING:

Deep Sea Mining: How Belgium is sinking to the bottom

17th October, 2pm, Online

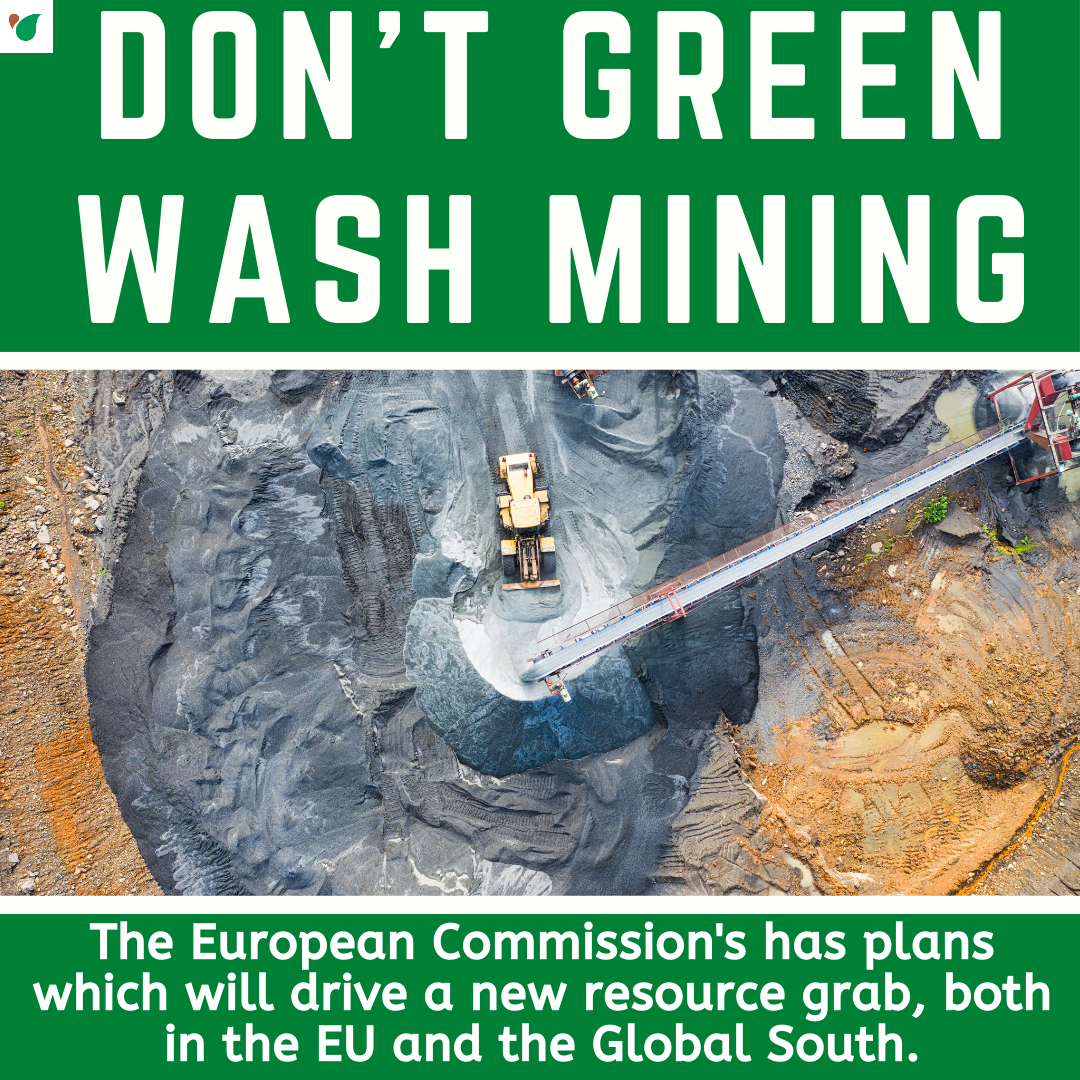

Our deep blue oceans are home to an unprecedented wealth of biodiversity, most of which is still undiscovered to the human race. However, Deep Sea Mining is threatening to destroy that. Experts and environmental movements fear irreparable damage.

Already over a million square kilometres is licenced for exploration in the Pacific, Indian and Atlantic Oceans. Belgium is one of the frontrunners in this field. The company DEME-GSR and the Belgium government are lining up to mine one of earth’s least known and untouched ecological habitats.

Find out about what Deep Sea Mining entails and which kind of threats it’s posing to ocean life. What part is the Belgium government playing in the birth of this destructive industry? And can we still stop this?

Arm yourself with knowledge on the threats Deep Sea Mining is posing and what we can do about it in Belgium, with speakers An Lambrechts from Greenpeace, Sarah Vanden Eede from WWF and Ann Dom from Seas at Risk.

Programme:

14:00-16:00 Webinar – Deep Sea Mining: How Belgium is sinking to the bottom.

16:00-18:15 OPTIONAL – Online public action training* (more info below)

You can view, invite friends and share the Facebook event here

You can find the Registration Form here

[Only registered participants will receive a joining link]

Online Public Action training workshop – Deep Sea Mining

*We have 20 spaces available for a separate Online Public Action training workshop.

This workshop is for citizens who are passionate about protecting our oceans and would like to become more involved in taking action to protect our blue planet from Deep Sea Mining and are already attending ‘Deep Sea Mining: How Belgium is sinking to the bottom’.

If you feel committed to taking action for a healthier blue planet for now and future generations to come and would like to be part of a passionate and active group of people with similar shared values working on the topic of Deep Sea Mining in Belgium, apply using the event registration form (found above).

The workshop will be held by CATAPA. The Deep Sea Mining Public Action workshop will follow on after Deep Sea Mining: How Belgium is sinking to the bottom ends.

It will take place from 16:15 – 18:15, 17th October 2020.

Send an email to communication@catapa.be introducing yourself.

Send an email to communication@catapa.be introducing yourself.