Art and unity in Cajamarca

Art and unity in Cajamarca

“What if we sing?”, she asks as she pulled a small paper with some scribbles that formed lyrics out of her pocket. She is one of the Defensoras de la Vida y la Pacha Mama from Cajamarca. We are in the middle of our latest workshop on citizen journalism and human rights and we are just chitchatting while lunch is being served. “What if we sing?”

And we sing. Not just to pass time waiting, but to get our message through, to come closer. Quickly the participants of the workshop gather together, have a look at the lyrics, and sing. About the beautiful lakes of Cajamarca, the mining projects destroying them, about their resistance, their fight and never giving up.

My mother and I wrote this song as we were protesting against Conga”, the woman tells us, “we sang it in the streets, we sang it everywhere. And it is still accurate

Human Rights

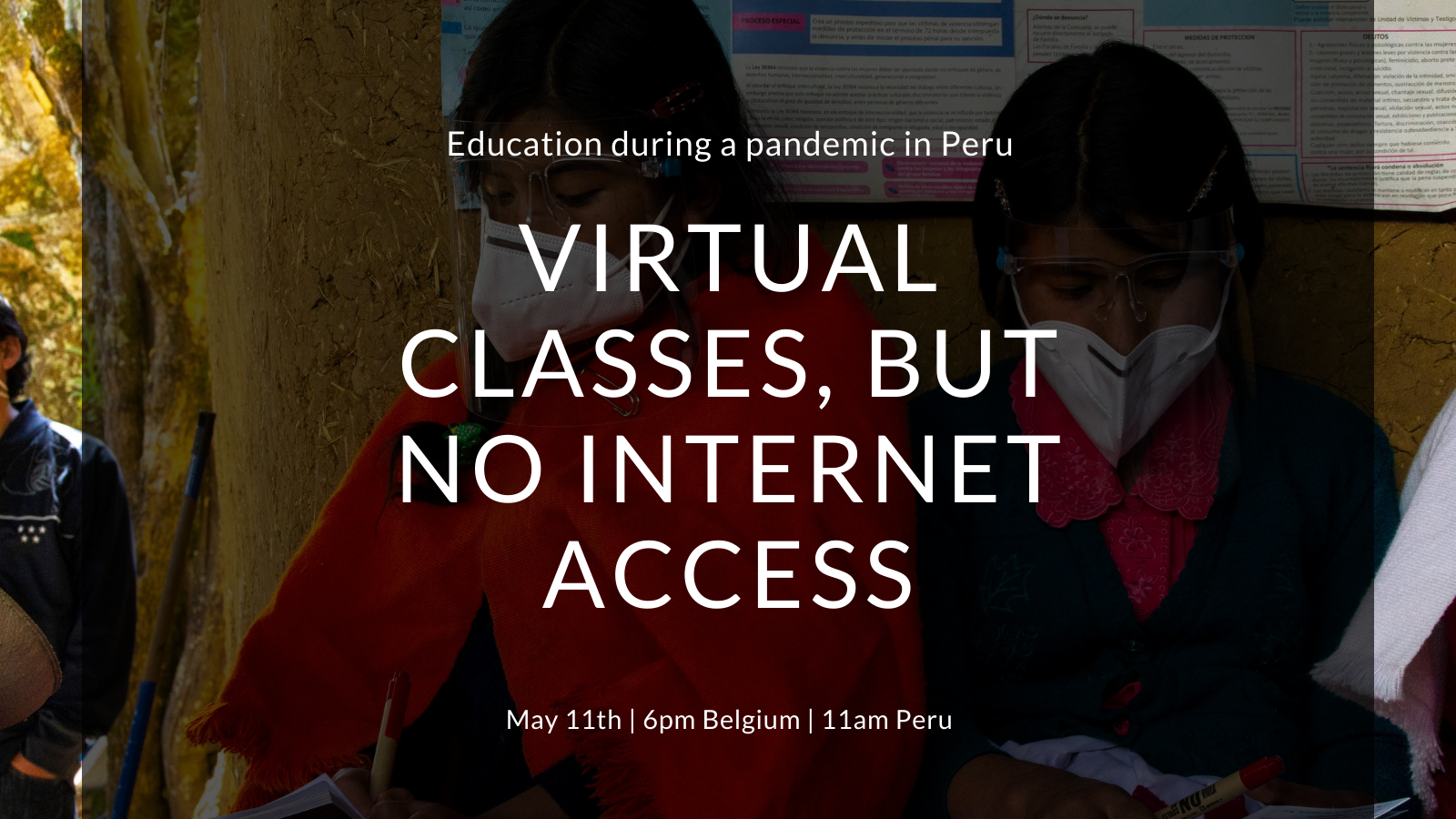

The song became the common thread during the rest of our workshop. We had come together in a training session organized by our partner organization Grufides in Cajamarca, Peru, together with Chaikuni in Iquitos, as part of a project financed by the province of Oost-Vlaanderen. It focuses on empowering rural and indigenous women for the defense of fundamental and collective rights in socio-ecological conflicts in both of these regions.

A big and important part of this project consists of organizing training sessions on two main topics: human rights and citizen journalism.

The first topic informs about human rights with the idea that “you can´t defend your rights if you don´t know them”. So that´s why for the last year and a half we have been working with people, mostly women, from different communities in Cajamarca on different matters: human rights, environmental rights, violence against women, intercultural health and so forth.

Coming together to talk about experiences in different communities is of great importance. It helps to know that people in other regions have to go through similar problems, to hear the outcome of similar struggles, and to know other communities support you in this fight to defend your rights.

Citizen Journalism

The second topic we work on during these training sessions is citizen journalism. How can these communities make sure the rest of the world knows what they are going through? How can they make sure everyone is aware of the cases they are fighting for?

Journalism and means of communication are important tools to address the violation of collective and fundamental rights in these communities. Nowadays, journalism can be one of the most powerful tools to defend your rights.

This is why during these sessions we focus on making videos, photographs, writing notes, making radio programs and radio spots. We learn about storytelling, how to use social media and hashtags and most importantly: we do this together.

Our main focus during the last few sessions was to work on a regional and national campaign between the different communities involved in this project. The participants themselves came up with goals for this campaign, with their target audience, and during this last session: their strategy.

Art as a strategy

The participants decided to focus on three specific cases for this first campaign and came up with four different strategies to reach their audience: a video, in which we could show a before and after related to the mining projects in their region, a study on the water quality, a key figure who can tell their story from their own perspective and last but not least, art.

We can paint. We can paint murals all over Cajamarca, all over Peru. We can sing, we can write more songs, like the one we just sang. We can use poetry. We can make theatre. We are all creative, we all have capacities. And we can use art as our strategy

The ideas on how to use art in our campaign kept flowing. “When Máxima Acuña was told to tell her story in the international press, she didn´t tell it. She sang it. And it was so much more powerful, it transmitted so many emotions. I still get goosebumps thinking about it,” someone said, “we can do this too. Our stories are powerful too. They just need to be heard.”

To end this day-long session, we asked the participants what they learned. “That together we are stronger”, someone said. “That we can use our art to let the world see our reality”, someone added. Art and unity. That´s what we learned today. Art and unity. We will stand together and sing. And our voices will be heard.