Multinational mining companies all over the world use similar strategies to convince communities to agree to their destructive extractive projects. Want to know their secrets?

We’re diving into the mining conflict currently occurring in the village of Falán, Colombia, where multinationals including Anglogold Ashanti are preparing the village for the mines they want to open there. The mining projects will have a devastating impact on the environment, access to potable water, agriculture in the region and the current and future potential of tourism.

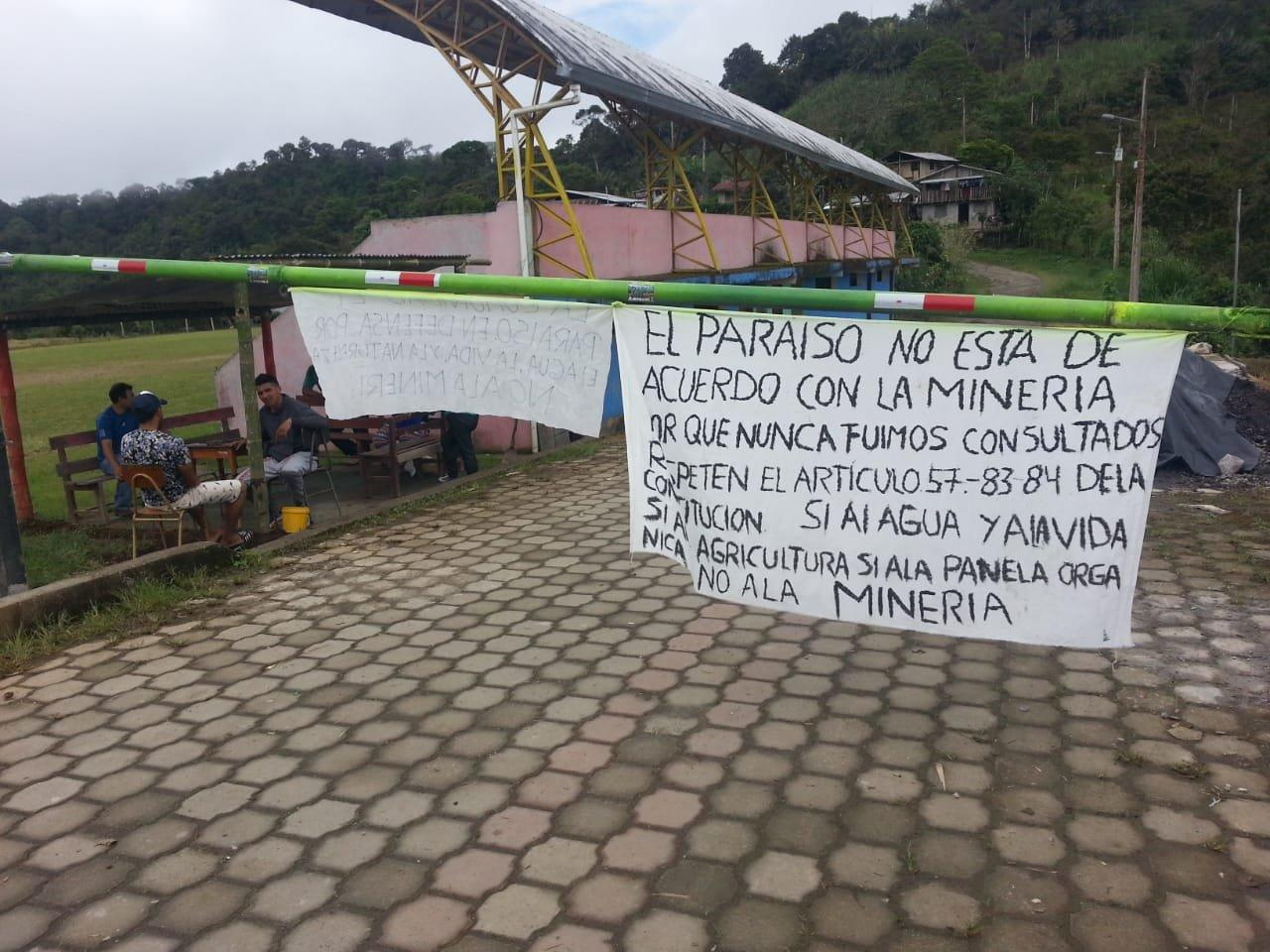

So you can imagine, it’s a hard sell for the families living in the region. Like thousands of other communities in the world, the inhabitants of Falán are resisting the upcoming extractive projects in their region, protesting to preserve their right to clean water and a healthy living environment.

Since no informed person would like an open pit mine close to their home and it’s totally rightful for them to resist, it’s not always easy for multinationals to expand their businesses in other countries. But if you too are an unethical multinational mining corporation looking to devastate a local community and the surrounding natural area and propel the climate crisis and social injustice, look no further.

Read the 8 steps below for a handy guide to dividing communities, sparking conflict and creating the exact amount of chaos necessary for your project to proceed.

Step 1. Think about a suitable name for your destructive project

For obvious reasons, your company might have a bad reputation in the region you’re tearing up. Here’s a quick fix: just create a sub company with a different name! Yes, it is that easy.

Anglogold Ashanti is using this strategy all over Colombia, where a lot of communities resist the company coming to their neighbourhood because of its reputation in other regions. Rather than waste time speculating on what that bad reputation might say about their business, they create sub-companies, with ambiguous legal ties, to start with the exploration phase in a certain region.

Take the case of Falán. In Falán a company named Miranda Gold is currently exploring the region, making holes 200 metres deep in the earth to check which mountains are ideal for gold extraction. Closer research strongly suggests that the company has ties with (and may get their funding from) Anglogold Ashanti.

The name game doesn’t end there. Each mine has a name, and to properly hide the horrifying impact it’s having, use a name that has a certain historical, cultural or environmental value for the communities that will be affected. With the proper branding, people can drink any poison.

What always works is just using the name of the mountain, the lake or waterfall that will be ‘replaced’ by your destructive project. Like the La Colosa mining project in Cajamarca named after the La Colosa waterfall. So, you don’t have to be original. Cultural appropriation at its finest.

For another good practice in this field we can go back to Falán. The village is rightfully very proud of their natural reserve called Ciudad Perdida, or Lost City, in English, that next to hectares of beautiful nature and waterfalls also houses the ruins of two mining villages from the 16th century. It’s a very unique ecotourism attraction that’s famous in the wider region.

Along comes another company performing exploration for extraction in the village (and that now has formed an alliance with Miranda Gold) in a clear nod to continuing a legacy of devastation, chose the name Lost Cities SAS to obtain licences to start exploring for valuable minerals in the area. Job well done.

Step 2. Get the local government on your side

It’s important to have local authorities on your side. They have a lot of power and influence and can bend local procedures to your advantage and pave the way for you. So don’t be afraid of corruption and paying off politicians in charge.

How to do this? First, understand how federal governments work. The appeal of a multinational lies in neoliberalism. This means, countries are viewed as ‘poor and underdeveloped’ or ‘rich and developed’ in terms of resource consumption. Bringing multinationals from ‘rich’ countries to ‘poor’ ones, federal governments hope, will bring in profit through taxes.

Then, pay off the local politicians to agree and hand out licenses, but also to actively fight opponents of the projects with threats (see step 7). Play into the downfall of democracy: limited political terms means the same politicians agreeing to the projects are not the ones that will have to deal with the situation of water scarcity, contamination and poverty created by the mining projects in a certain amount of time.

Important point: make sure there’s no paper trail or legal basis holding you responsible for the impact of your project on the environment or human rights.

3. Lobby as much as possible to bend the law in your favour

Sometimes your destructive mining project might find itself facing pesky ‘legislation’ to defend the rights of communities to decide over their lands, or to protect the environment, or some such thing.

As someone interested in none of those things, now is the moment to form alliances with other multinationals. Take those funds – around the amount that would restore a significant area of the rainforest – and pour it into government lobbying to create legal loopholes for corporations. Behind closed doors, of course – wouldn’t want the public to know about this.

Take Colombia for example. In Colombia communities had the constitutional right to organise referendums and take decisions about their lands. Because of that law and lots of communities standing up for their rights, several mining projects were prevented from happening.

But thanks to a strong mining lobby, in 2018 the (unconstitutional) decision came that these referenda can’t be organised anymore for mining projects. Because that’s a matter of national interest, that transcends the stakes and interests of a local community. There have to be some sacrifice zones for others to live a wealthy lifestyle. Remember: good corporate lobbying doesn’t rely on logic or science.

Also locally there are often regulations and procedures that you have to take into account for the completion of your project and, if needed, bend to your advantage. In Colombia for example every municipality has a POT (Plan de Ordenamiento Territorial) in which they decide for a certain amount of years what their land can be used for. The POT of Falán for example only allows agriculture and tourism. But luckily Anglogold has his friends within the city hall (see step 2) and they are currently working on revising the plan for mining to be added as a way of using the land.

4. Presents! Buy off public opinion

Presents. Always. Work. Especially in areas where the access to information about the impact of mining is limited, so these are the areas that are often easier to win over.

Remember to only give gifts that also benefit you, like promises to build better roads (that your company will need to transport the metals and minerals). Those are a win-win for everyone. When in doubt, just hand out money.

The saying goes ‘there’s no such thing as bad publicity’, so make sure your company and project name gets spread as much as possible. Children are our future leaders, don’t forget about them. They are also an easy means to, through their school, reach whole families.

Mirandagold (or should we say Anglogold? It’s hard to tell the difference) is champion in handing out gifts. In Falán there’s records of farmers getting machetes, food and money. They even created a special game for the children in Falán on the day of Halloween, through which they could win tablets! They handed out toys with their company logo to children through the local school. A great way to make some extra publicity. Who says love can’t be bought?

5. Create chaos and conflict, divide the community in two camps

So you gave out gifts, but probably didn’t win over everyone, right? Don’t worry. There’s other strategies that you can apply too. This is where the next step comes in: divide and conquer. Make sure there’s conflict between the groups in the communities. Feed that conflict. Use your imagination.

In Falán, Mirandagold fired 100 employees at the same time. All of them, coincidentally, were residents of the municipality and this happened, coincidentally, at a moment where protests against the mining project were heating up. This is a good way of showing families how dependent on the mining project lots of them are, and to feed resentment against those protestors portrayed as the cause of the dismissals. And if there are too many activists against the project, well, take a look at step number 7.

6. Prepare the local community well for a lack of access to potable water in the future

The impact of big scale mining on the water resources in the wider region is tremendous: water scarcity due to the huge demand of the extraction process, dried out lakes and rivers, contamination of rivers and ground water with heavy metals and toxic substances…

But of course, having access to sufficient and clean water is important for health, for agriculture, and for life in general. Local communities can’t drink gold. So if you’re planning to deprive a community of clean water, the trick is to prepare them ahead of time and disguise the link to the extractivist mining. This is a good moment to suddenly feign interest in climate change and shift responsibility there.

That’s exactly what happened in Falán. Recently, different regions have experienced a lack of water for up to five or six days at a time. The local government attributed the scarcity to climate change. Which is weird, because it rains almost every day there, and a lot.

Also weird is that the companies that are exploring in the region (and need a lot of water for that) continue to have water for their operations, they don’t experience the same inconveniences as the inhabitants.

7. Threats are effective deterrents

Struggling with these do-gooder environmentalists fighting your development project? Why listen when actions speak louder than words?

Threaten them. Go by their houses, let them know you know where they live. ‘Reason’ with them. Preferably accompanied by a large group of intimidating-looking men. Focus on the leaders of the struggle. Scaring people works. Especially in Colombia, since it’s one of the most dangerous countries in the world for human rights defenders. Last year 186 were killed, which is almost half of the global total registered number.

In Falán, people received intimidating visits from workers of the mining company and even death threats. For that last one the pro-mining local government even sent the police (and true to the previous steps, despite the clear benefit this brings to MirandaGold, the lack of paper trail makes it impossible to prove a connection).

8. Having wreaked havoc, now frame it as a successful story of ‘growth’

Effective communication to portray yourself as a hero means a lot of empty keywords. Describe your project in terms of ‘growth’ and ‘development’. Because who doesn’t want growth and development? Those words mean prosperity, welfare and jobs – right? Just don’t mention anything about the disastrous effects of unchecked growth for both people and the planet. And obviously no need to mention that the prosperity and income from said corporate growth aren’t meant for the local community or those poorer countries. Regardless of how it is shared, communicate that obviously a bigger cake is always desirable. Certainly omit to mention that you got out of paying most of the taxes required of multinationals. And avoid putting emphasis on the fact that the jobs are short term, while the environmental damage is forever.

Now it’s up to you

With these steps for success, you will push through your big scale destructive mining project in no time. Let us know if there’s other tactics we should add to the list!

Corruption, abuse of power, threats, Trojan horses, what is happening in Falán is also happening all over the world.

But resistance is strong. Communities are resisting and fighting for a better world for themselves, their children and for future generations. The inhabitants of Falán are ready to take action and have alternative plans for the future of their village.

Follow Colectivo Ambiental Falán y Frías and Catapa (Instagram/Facebook) to keep up to date on the situation in Falán and other struggles against mining multinationals. You can also join the Catapista volunteer movement and take up an active role in the strive towards a society within the boundaries of both people and planet, towards a world in which mining is no longer necessary.

There is also a new campaign launched by the Network of Persons Affected By Anglogold to denounce and unmask the unethical and violent behaviour of the multinational and demand that they leave Colombian territory. In a web series called ‘Historias Quebradas’ they unveil the malpractices and secrets of Anglogold Ashanti in Colombia. Check out their website and discover how you can support them!

This article is the result of a research project conducted by volunteers from CATAPA’s study and lobby working group in collaboration with Colectivo Ambiental Falán y Frías.