Ecuador: Extractivism in the midst of an Economic and Sanitary crisis – COVID-19

Ecuador: Extractivism in the midst of an Economic and Sanitary crisis (COVID-19)

Author: Kim Baert

Ecuador is one of the most affected countries in Latin America by COVID-19, after Brazil and Peru. At the time of writing (14 May 2020) the official figures show 30,502 confirmed cases and 2,338 deaths. These numbers are questioned from different angles, because they probably do not represent reality. Ecuador, but also other countries in Latin America, have a huge backlog in testing large parts of the population for the virus, and the death toll is expected to be much higher than indicated.

The epicentre of the epidemic in Ecuador is located in the harbour city of Guayaquil, the second-largest city in Ecuador. At the end of March, the first images appeared of corpses wrapped in plastic and left behind in streets and rubbish bins as well as images showing cardboard boxes used to store the bodies. These shocking images were shared all around the world. In March, the city counted more than 70% of all confirmed cases in the country, a number that has since fallen to 55%. Quito, the capital city (province of Pichincha) is the region hardest hit after Guayaquil, but like other parts of Ecuador has been spared of similar disaster scenarios.

Sanitary emergency plan vs. economic malaise

President Lenin Moreno came under heavy pressure. Numerous organisations and members of the civil society wondered how the government would deal with this health crisis. After all, COVID-19 is a major challenge for a country that is already in an economic and political crisis. The towering external debt and falling oil prices place Ecuador in a particularly vulnerable position.

The huge external debt and a scheduled repayment in March 2020 led to a petition from civil society and the Ecuadorian parliament to postpone the debt repayment to be able to spend more resources on the health system. The Ecuadorian government did repay $325 million on 24 March 2020. The most important creditors are the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the World Bank and China. This repayment caused a lot of criticism in Ecuador because it made clear to many that the current Moreno government does not consider the health of its citizens a priority. After several negotiations between Ecuador and the creditors, other debt repayments were put on hold. Additionally, emergency financial assistance was requested from the IMF to deal with the current health crisis.

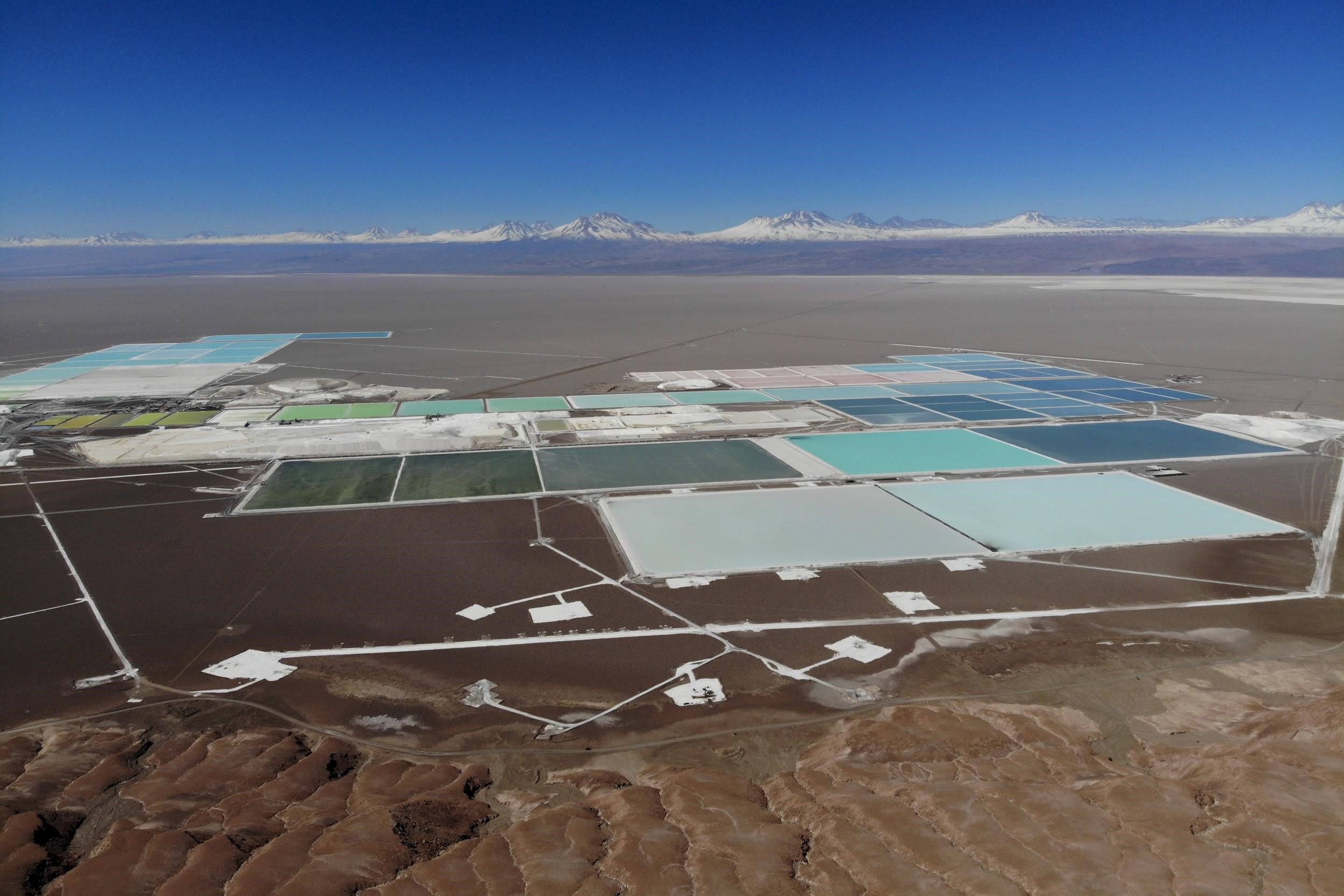

The falling oil price caused additional damage to an already fragile national economy, which is mainly dependent on oil exports. The sector has suffered quite some losses in recent months. The corona crisis, the falling demand for oil, and the subsequent conflict between Saudi Arabia and Russia, led to a fall in the global oil price and dealt a severe blow to all oil exporting countries, including Ecuador.

Moreover, the further course of the corona crisis has led to an historic event. On 20 April 2020, the oil price of the American WTI (West Texas Intermediate) fell to as much as – $37 per barrel, a price well below zero. The WTI serves as a benchmark for the oil price in Ecuador, where the same trend occurred. This negative price can be explained by a low demand for oil products and the lack of storage space to store the oil barrels.

Oil spill in the Ecuadorian Amazon

On top of the crash in oil prices, the oil industry suffered another heavy blow with a major ecological impact. On 7 April 2020 – in the midst of the corona crisis – an oil spill caused serious damage to the northern Amazon of Ecuador, more specifically on the border between the provinces of Napo and Sucumbios.

The cause of the leak was the rupture of several oil pipelines, including the SOTE (Sistema de Oleoducto Transecuatoriano), OCP (Oleoducto de Crudos Pesados) and Poliducto Shushufindi-Quito. The rupture occurred because of erosion in the river Coca causing landslides and damaging the pipes.

The companies Petroecuador and OCP immediately announced the suspension of oil production. Now, a month later, they are increasing the production rates again even though no clear measures have yet been taken to remedy the social and ecological damage caused by the leak.

The region, where the oil spill occurred, is considered a high-risk zone. Already during the construction of the oil pipelines, environmental organisations such as Acción Ecológica and experts in geology had warned about the possible adverse ecological and social consequences. Indeed, the oil spill is considered a huge risk as its course is passing the active volcano Reventador as well as three protected national parks (Cayambe Coca, Sumaco Napo Gelaras and Yasuni). The social impact of the rupture is also significant: the spill’s course crosses populated centres and pollutes not only the Coca river but also its tributaries, leaving more than 35,000 people without clean water. A disaster that has become all the more critical during the COVID-19 crisis.

Mining in times of Corona

In response to the current economic and sanitary crisis, the Ecuadorian mining sector has put itself in the spotlight as the only salvation from this precarious situation. Compared to the long history of the oil sector, mining is a relatively new industry in Ecuador, although it has a similar social and environmental impact.

The government took fairly strict measures to protect public health from COVID-19 in mid-March, but they appear not to apply to everyone. The mining companies operating in Ecuador indicated that they would temporarily suspend their activities because of the COVID-19 outbreak. In practice, however, operations continued.

Moreover, the mining sector abused the quarantine measures in order to put material for further exploration and exploitation on their sites. This happened at various locations in the country. In the province of Pichincha and more specifically in the Pacto region (DMQ), a mining company used the emergency situation on 16 March to install new machinery. These developments would not have been possible under normal circumstances, due to resistance from the local population.

The mining and oil industries are considered strategic sectors in Ecuador and have therefore been given a ‘carte blanche’ to continue their operations. This provoked a lot of criticism because this way mining companies are putting local and indigenous communities at risk. According to MiningWatch Canada, mining camps pose a major risk to the further spread of the coronavirus, despite current measures. Moreover, the regions where mining takes place are often remote from adequate medical facilities and there is less access to safe drinking water. For example, the indigenous Shuar community, located in the southern provinces of Ecuador (Morona Santiago and Zamora Chinchipe), reported that the presence of mining companies puts them in a very vulnerable position.

The two largest mining projects in the country, Fruta del Norte (gold mining) and El Mirador (copper mining), which officially started the excavation and production of gold and copper in 2019, have reduced their number of employees on-site by more than half. Local authorities in the province of Zamora Chinchipe, where the projects are located, had called for a temporary suspension of production in order to reduce transport and relocation in and out of the site. El Mirador responded to this call and in the meantime decided to focus on building a second tailings dam (‘Tundayme’) to store chemical waste. Once the corona measures are lifted, El Mirador will again increase its production to full capacity.

The recent collapse of the oil industry in Ecuador raises questions about the dependency on crude materials and the rigid adherence to non-renewable and finite energy sources. There are also concerns among environmental organisations about the rapid rise of the mining sector, which promises to lead the nation out of the crisis, but which, like the oil industry, is causing enormous damage to local communities and the environment. In the past decades, Ecuador has suffered enormous impacts because of its dependence on the extractive industry, a reality that has been confirmed once again by the current economic and sanitary crisis.

Read more about how the COVID-19 health crisis is affecting Peru, from the first Ten days of quarantine till the current situation in the Peruvian Amazon.