Lands in Resistance: Mining and the voices of communities through the power of documentary cinema

Written by Francesca Serafini

As part of the Right to Say No Campaign, we hosted the Lands in Resistance documentary screening and discussion that gave voice to those who rarely make it to the mainstream stage: communities directly affected by mining projects. Instead of boardrooms and parliamentary halls, these stories come from mountains, forests, and communities under threat. We presented two powerful documentary films:

- The Illusion of Abundance by Erika Gonzalez Ramirez and Matthieu Lietaert

- Savanna and the Mountain by Paulo Carneiro

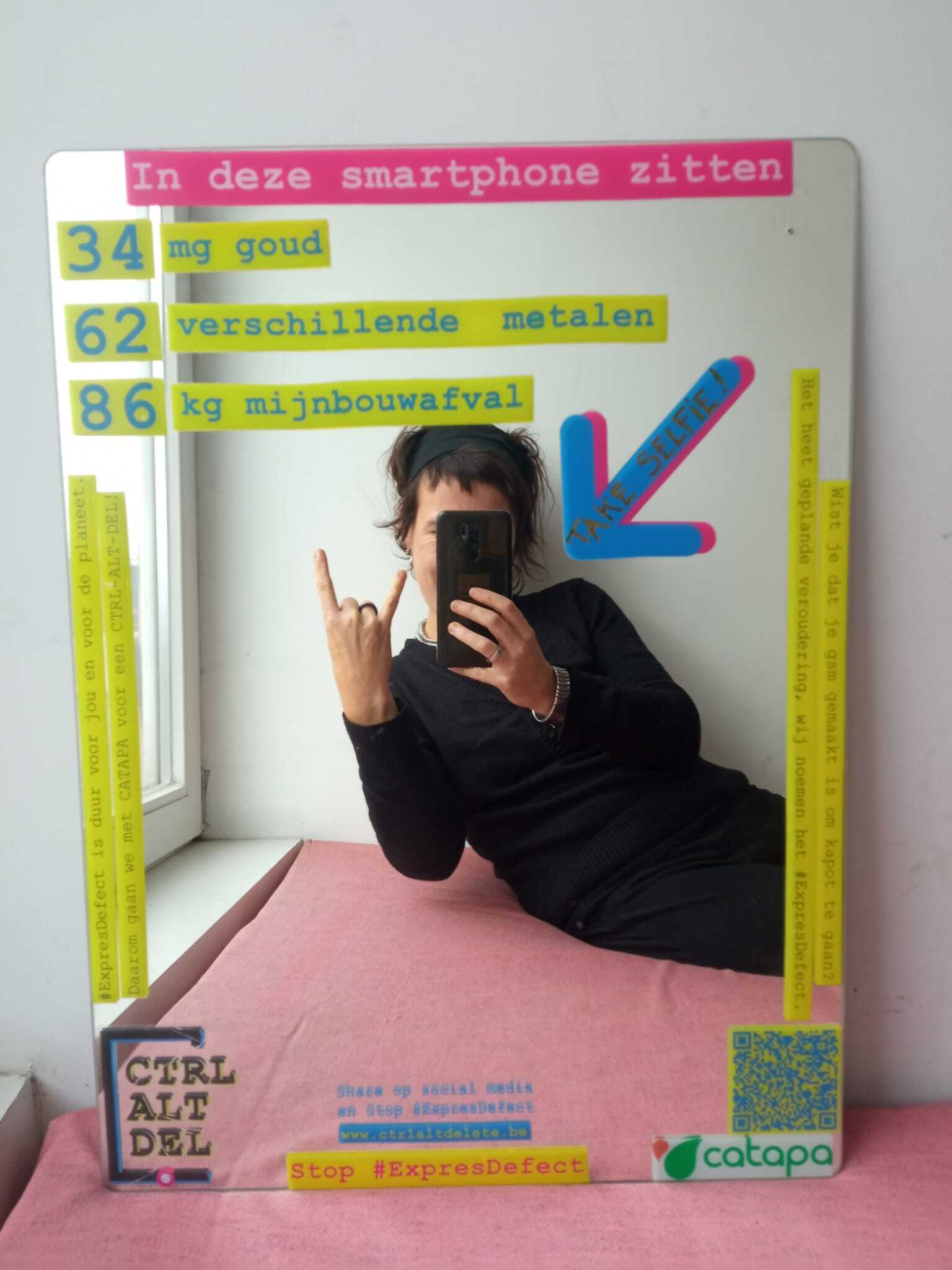

At a time when the so-called green transition is accelerating, with politicians calling for more mining to extract lithium and other materials for a “cleaner future,” we ask:

At what cost? Whose land? Whose health? Whose life?

Before the lights went out…

Before the screenings began, we shared heartfelt video messages from the directors, offering their insights and intentions behind each work. These personal introductions framed the evening and reminded us that filmmaking is also a form of activism.

After the screening…

We invited the audience to share their thoughts and reflections on cards, some of which we share below. These contributions were a fundamental part of the collective experience we created around the screenings. They offered not just reactions, but deep and often emotional responses that enriched the space of dialogue and connection.

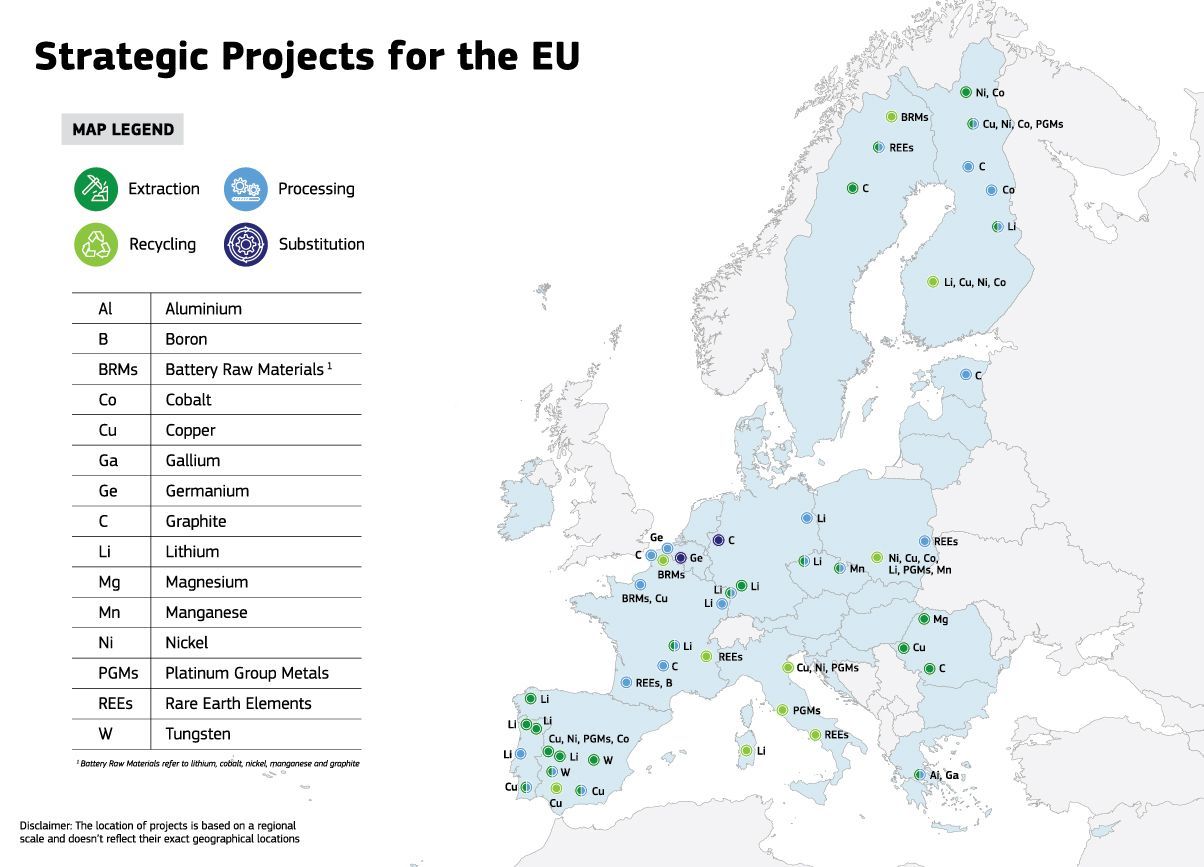

Beyond the reflection cards, spontaneous discussions also emerged, particularly after the screening of the first documentary on mining in the Global South. The conversation quickly expanded to include extractivism as a broader issue, not only affecting communities in the South but also increasingly present in the Global North. The audience reflected on the European Union’s role in the ongoing expansion of extractive activities. In the race for critical raw materials to fuel the green transition, the EU has selected a list of mining projects under the Critical Raw Materials Act.

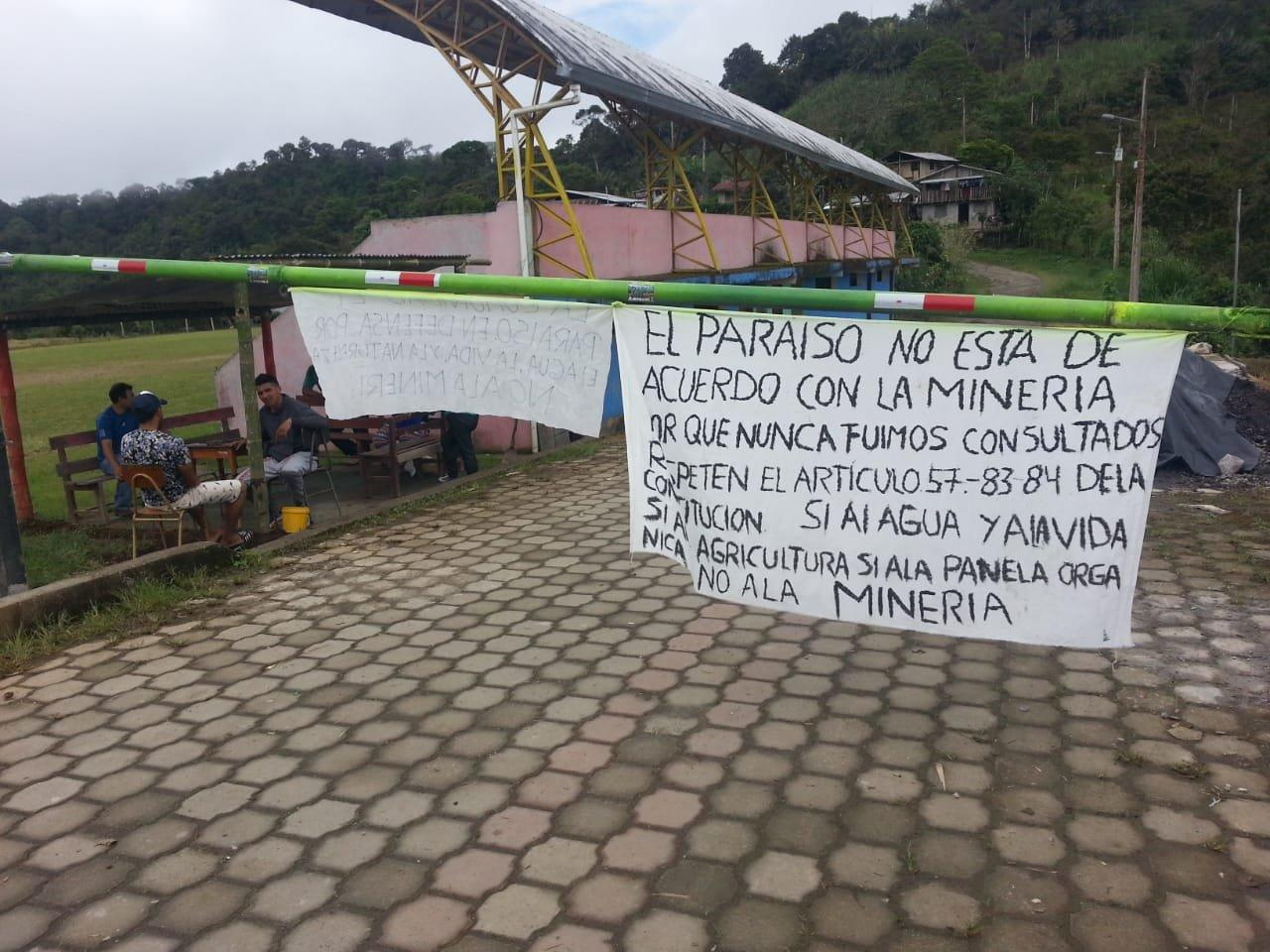

A small detail? Local communities were not consulted during the decision-making process. Among the selected projects is a mining project in Serbia, developed by global giant Rio Tinto, which disregarded the will of the Serbian people. The Act also includes the project featured in the film Savanna and the Mountain that local populations have been resisting for years. Hence, this conversation naturally anticipated the themes explored in the second film, Savanna and the Mountain, creating a sense of continuity and connection between the two screenings.

Screening of the Illusion of Abundance at Pangea, KU Leuven on the 11th March

The Illusion of Abundance

This film follows three women from Honduras to Brazil to Peru: Bertha Cáceres, Carolina de Moura, and Máxima Acuña. They confront some of the world’s most powerful transnational corporations. Despite constant threats, repression, and personal risk, they continue their fight to defend their communities, their environment, and their future. It’s a film about courage and imbalance: how those who profit from destruction are rarely held accountable, and how those who resist are often the ones who pay the price.

And the audience reacted powerfully.

From the frustration and sadness in the face of fundamental issues that are still too little known and discussed,

“It makes me sad not to have known about this. People are being killed, and we hear nothing.”

A driving force towards action also emerged, leading to a reconsideration and expansion of knowledge:

“I’m from Bolivia, and I saw so many parallels with what’s happening there, especially how governments prioritise mining over human rights.”

“The movie challenges my assumptions about development actors! And it highlighted how much more organised and widespread environmental activists are in the Global South, more than is perceived in Europe.”

“Thank you for bringing this to our attention. We need to change our way of life.”

And finally, some felt the strength and hope that come from action and connection. Inspired by the empowerment of communities resisting, many found new courage and motivation.

“This movie inspired me deeply in the sense that I always thought it was too difficult, not to say impossible (or even useless) for communities to resist against corporations because it feels like nothing can change, BUT IT ACTUALLY CAN.”

“The courage of these women is inspiring. They don’t sell out, no matter what’s offered to them.”

Screening of Savanna and the Mountain on the 30th March in Filmhuis Klappei, Antwerp

Savanna and the Mountain

Set in Covas do Barroso, a village in northern Portugal, this docu-film follows the residents as they organise to resist the planned construction of Europe’s largest open-pit lithium mine by British firm Savannah Resources. It’s a poetic and politically sharp film where the villagers themselves reenact their struggle through songs, theatrical acts, and seasonal rituals. Part documentary, part ballad, Savanna and the Mountain becomes a collective act of storytelling and resistance, intensely local, yet globally resonant. Some of the most inspiring quotes from the audience’s reactions:

“I did not know there are mining projects in Europe. I believed they were predomintanly outside of Europe”

“I’m scared by the scale of power involved in these mining projects”

“Sometimes the Green Deal just seems like a good excuse to exploit and extract more and more…”

“This was my first time hearing about it, and it really opened my eyes.”

“Songs are such a powerful tool of resistance and of people coming together”

“No pasarán” (“They won’t pass”)

Resistance is not a slogan: it’s a practice

Both films shed light on the injustices and struggles faced by communities who are forced to bear the consequences of a lifestyle that benefits others, often far away from the mines, dams, or damaged lands. These stories remind us that behind every battery, every megaproject, there are real people, often silenced, fighting for their land, their rights, and their lives. They are resisting, and their voices need to be heard. In cultural projects like this screening series, we want to raise awareness and amplify their voice, helping these communities defend their “right to say no”.

Cinema and art in general are not just entertainment; they’re a mass vehicle for truth, resistance, and collective awareness. Especially now, in a moment of geopolitical shift when Europe is making significant decisions about its extractive future, it is more important than ever to centre the voices of those affected first and foremost. Their lives, land, and resistance must be part of the conversation. We are deeply grateful to everyone who joined us, shared their reflections, and helped create a space where these powerful stories could be seen and heard.