Lithiumexploitatie droogt de ’s werelds droogste woestijn uit

Lithiumexploitatie droogt de ’s werelds droogste woestijn uit

Dit artikel is een samenvatting van een langer onderzoeksproject van Danwatch, gepubliceerd in samenwerking met CATAPA en SETEM. Meer informatie aan het eind van dit artikel.

De Acatama-woestijn in Chili, ’s werelds droogste woestijn, is haar laatste watervoorraden langzaamaan aan het verliezen. Inheemse gemeenschappen trekken al enkele jaren aan de alarmbel en worden nu gesterkt door wetenschappelijke onderzoeken en milieuorganisaties. Oorzaak van deze uitdroging? Lithiumwinning.

Lithium is essentieel voor de batterijen in onze telefoons, onze computers en de explosieve toename van het aantal elektrische voertuigen die vaak worden gezien als de sleutel tot een groene energietransitie. Chili, dat over de helft van de lithiumreserves ter wereld beschikt, is uitgeroepen tot ‘Het Saudi-Arabië van het Lithium’ en bijna de gehele export wordt momenteel gewonnen uit de Atacama-woestijn, de droogste plaats ter wereld. Maar het winnen van Atacama’s lithium brengt met zich mee dat enorme hoeveelheden van de schaarse watervoorraden worden opgepompt. Watervoorraden die ervoor gezorgd hebben dat inheemse volkeren en dieren duizenden jaren in de woestijn hebben kunnen overleven.

Volgens onderzoekers veroorzaakt de extractie nu al blijvende schade aan de kwetsbare ecosystemen van het gebied. In de Atacama en elders in Chili protesteren de inheemse gemeenschappen nu tegen de huidige en toekomstige plannen voor lithiumwinning. Veel gemeenschappen beweren dat ze nooit geraadpleegd werden vóór de winningsprojecten, hoewel de Chileense autoriteiten verplicht zijn dit te doen volgens de internationale verdragen die door de Chileense staat geratificeerd zijn. Het Deens onderzoekscentrum Danwatch kan documenteren dat bedrijven zoals Samsung, Panasonic, Apple, Tesla en BMW batterijen krijgen van bedrijven die Chileens lithium gebruiken.

Met de onvergelijkbare lithiumreserves van het land en het steeds belangrijker wordende belang van het metaal voor de energiesector, heeft Chili af en toe het label ‘Het Saudi-Arabië van het Lithium’ gekregen. Bijna 40 procent van het wereldwijde aanbod komt de afgelopen 20 jaar uit Chili en, zoals Danwatch kan onthullen, komt het terecht in een aantal van de populairste elektronica en elektrische auto’s. Het metaal is een van de meest populaire producten van de Chileense energiesector.

De inheemse gemeenschappen van de Atacama werden echter in snelheid gepakt. Chili heeft ILO-conventie 169 ondertekend, die de regeringen verplicht om de inheemse bevolking te raadplegen wanneer grote projecten in hun omgeving worden uitgevoerd. Maar volgens de inwoners van Pai-Ote werden ze niet geraadpleegd voordat de lithiumprojecten in de media werden gepresenteerd. “We ontdekten via de pers dat er een overeenkomst was gesloten die SQM in staat stelde om hier aan lithiumwinning te gaan doen. Niemand vroeg het Colla-volk of ze de mijnbouw op hun grondgebied wilden”, zegt Ariel Leon, vertegenwoordiger van de Colla-gemeenschap.

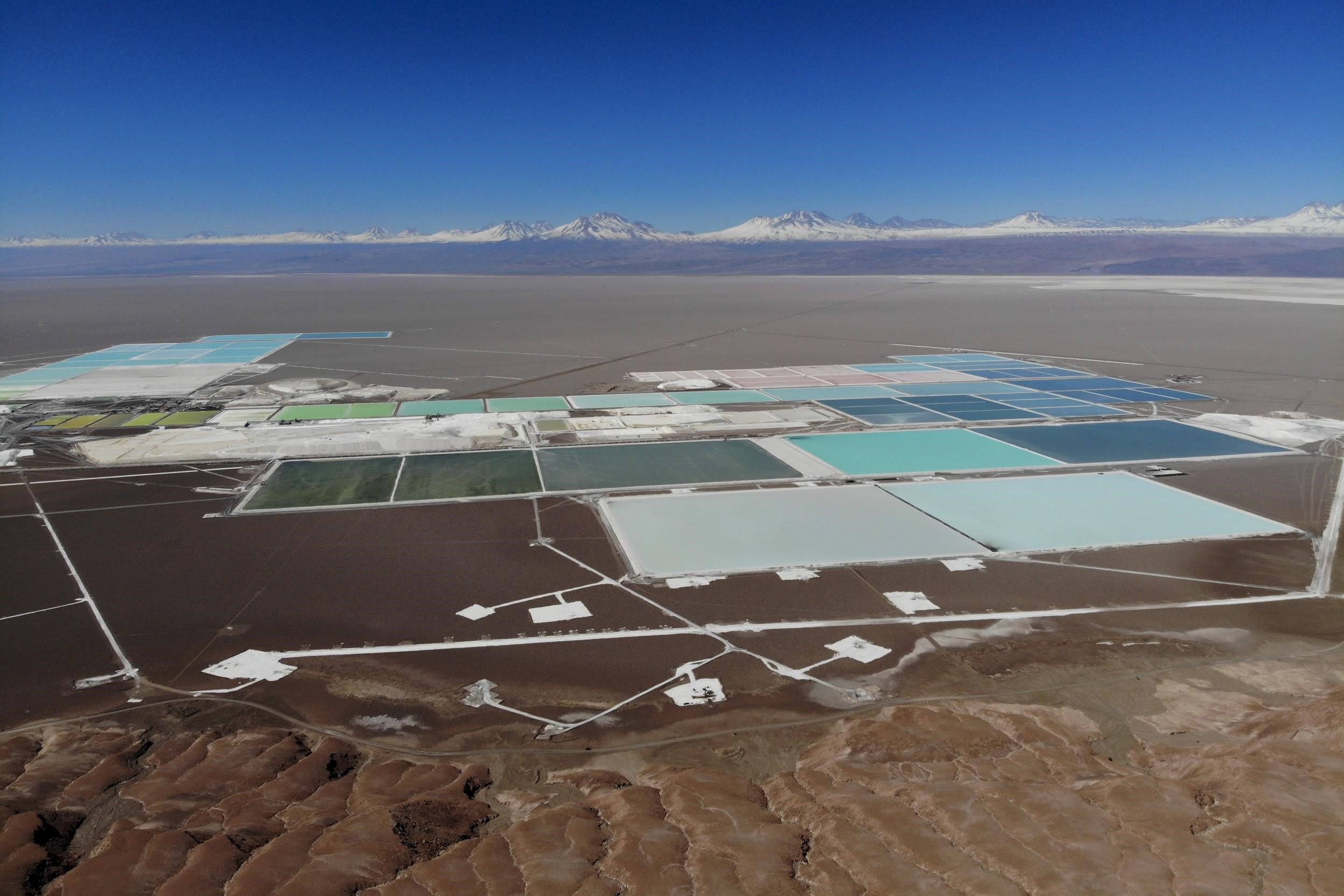

Het Chileense lithium kan tegen lage kosten worden gewonnen: mijnwerkers pompen lithiumhoudende pekel uit een massief reservoir onder de Atacama-zoutvlakte naar enorme plassen op het oppervlak van de woestijn. De hoogste zonnestraling ter wereld zorgt ervoor dat het water van de pekel snel verdampt, waardoor het lithium samen met andere zouten en mineralen wordt opgeschept.

Tijdens dit proces verdampt tot 95 procent van de gewonnen pekel in de lucht. Dit versnelt de waterschaarste in de Atacama, zegt Ingrid Garces, een hoogleraar techniek aan de Chileense Universiteit van Antofagasta, die onderzoek doet naar zoutpannen. “In Chili wordt lithiumwinning beschouwd als een normale vorm van mijnbouw, alsof je een harde rots aan het winnen bent. Maar dit is geen reguliere mijnbouw – het is waterwinning”, zegt ze.

De twee bedrijven achter de lithiumwinning in de Atacama, de Chileense Soc. Química & Minera de Chile (SQM) en het Amerikaanse Albemarle Corp. hebben vergunningen om bijna 2.000 liter pekel per seconde te winnen. Naast de pekel winnen lithiummijnwerkers ook aanzienlijke hoeveelheden zoet water samen met de nabijgelegen kopermijnen. “Het gevolg is een impact op de biodiversiteit in het algemeen. En dat effect is nu al te zien – de wetlands drogen uit”, zegt Ingrid Garces.

Atacama’s inheemse gemeenschappen luiden al jaren de alarmklok over waterschaarste. Volgens de Atacama volksraad, die 18 inheemse gemeenschappen vertegenwoordigt, zijn de afgelopen tien jaar rivieren, lagunes en weiden allemaal in hoeveelheid water afgenomen. De Chileense autoriteiten hebben echter grotendeels vertrouwd op de milieueffectrapportages van de mijnbouwbedrijven zelf. En deze studies hebben over het algemeen geen significante effecten op het waterpeil of de omliggende natuur vastgesteld.

“Voor de lokale bevolking is de verandering heel erg duidelijk. Ze merken dat er minder water voor hun dieren is en ze zien hoe de rivieren uitdrogen. Deze anekdotische kennis wordt niet serieus genomen door de bedrijven of de staat”, zegt Cristina Dorador, bioloog en universitair hoofddocent aan de Chileense Universiteit van Antofagasta die het microbiële leven in de Atacama bestudeert.

In augustus 2019 kwam een analyse van satellietbeelden door het satellietanalysebedrijf SpaceKnow en het wetenschappelijke tijdschrift Engineering & Technology toch tot een vergelijkbare conclusie. Op basis van satellietfoto’s uit de periode van 2015 tot 2019 zagen zij een sterke omgekeerde relatie tussen het waterniveau in de lithiumvijvers van SQM en de omliggende lagunes: “Toen het waterniveau in de SQM-vijvers toenam, zou het waterniveau in de lagunes dalen”.

De ironie wil dat de Atacama-zoutvlakte ooit een groot meer was, voordat het duizenden jaren geleden door ernstige klimaatveranderingen opdroogde. Wetenschappers bestuderen de woestijn vandaag als voorbeeld van wat er met ecosystemen elders op de planeet kan gebeuren als de wereldwijde klimaatverandering effectief wordt. Maar in het streven om de stijgende temperaturen met elektrische auto’s te temperen, zuigen de industrieën het weinige water dat nog over is in de droogste woestijn ter wereld weg.

Danwatch, SETEM en CATAPA deden onderzoek naar de impact van de lithiumexploitatie in kader van het Europese Make ICT Fairproject. Deze campagne wilt de toevoerketen van onze elektronica zichtbaar maken en beïnvloeden door samen met publieke aankopers van ICT mijnbouw-en assemblagebedrijven om betere milieu-en arbeidsvoorwaarden te vragen. Lithium, als één van de belangrijkste metalen in de transitie naar groene economie, vormde de focus van dit artikel.

Danwatch is naar Chili geweest om de groeiende lithium extractie industrie van het land te onderzoeken. Daarbij werd groot aantal wetenschappers, bedrijven, politici en mensen die het dichtst bij de ontginningsgebieden wonen, geïnterviewd. Ze hebben de impactstudies van de mijnbouwbedrijven en de weinige onafhankelijke onderzoeksrapporten over dit onderwerp bestudeerd. Ze baseren zich vooral op onderzoek uit 2019 naar lithiumwinning in Chili door onderzoekers van de Arizona State University’s School of Sustainability.

Het onderzoek wordt ondersteund door het Make ICT Fair project, dit is gefinancierd door de EU. Publicatie gebeurt in samenwerking met SETEM en CATAPA.

TOESTELLEN DIE DE WOESTIJN UITDROGEN

Bekijk hieronder alle artikels uit het onderzoeksproject.

ARTIKEL 4: Er zit waarschijnlijk Chileense lithium achter het scherm waarop u dit leest.

ARTIKEL 5: Hoeveel water wordt er gebruikt om de batterijen in de wereld te maken?

ARTIKEL 7 / VIDEO: Bekijk de surrealistische lithium extractie landschappen van bovenaf.